Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

From the bomb to the moon: a retrospective gathers six decades of work.

Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory, installation view. Image courtesy Met Breuer.

Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory, Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue, New York City, through January 12, 2020

• • •

Vija Celmins’s current retrospective at the Met Breuer, To Fix the Image in Memory, begins with a small painting of an envelope, which the museum has cordoned off with an awkward stanchion. The painting is hung to the right of the introductory wall text, like an illustration, but it’s lushly rendered in a way that few of the artist’s other works are. The first time I saw it I was reminded of Wayne Thiebaud’s impastoed canvases of cakes and ice creams, but here the scene is solemn and gray (no sweets). The envelope is opened—the flap juts out to the right at a sharp angle, casting a dark shadow—but we can’t tell if the letter’s been taken out, and since the envelope is face down we can’t see who sent or received it. (The red, white, and blue lines checkering the border tell us it’s airmail.) The work possesses a vague idea of connection, but what comes across more strongly is a failure—or refusal—to communicate.

Vija Celmins, Envelope, 1964. Oil on canvas, 16 1/4 × 18 inches. © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery.

What can a painting say? What can it do? Celmins troubled over these questions in the work she made in the mid-1960s, when painting itself was in question. She started with things lying around her Venice Beach studio—a two-pronged office lamp, a hot plate, a TV (showing three planes nosediving)—depicting them, on modest canvases, in shallow, sepulchral space. A lot of artists talk rhapsodically about California light, but Celmins latched onto mundane appliances in drab interiors. Jasper Johns made gray paintings and sculptures of common objects, too, and Celmins cites the elder artist’s influence. But where Johns’s lightbulbs resemble fossils, Celmins’s technologies are illuminated: Heater (1964), plugged in, glows a dull orange. Hot Plate (1964) does, too. With rare exceptions, Celmins only uses color when her subject is fire and heat.

Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory, installation view. Image courtesy Met Breuer.

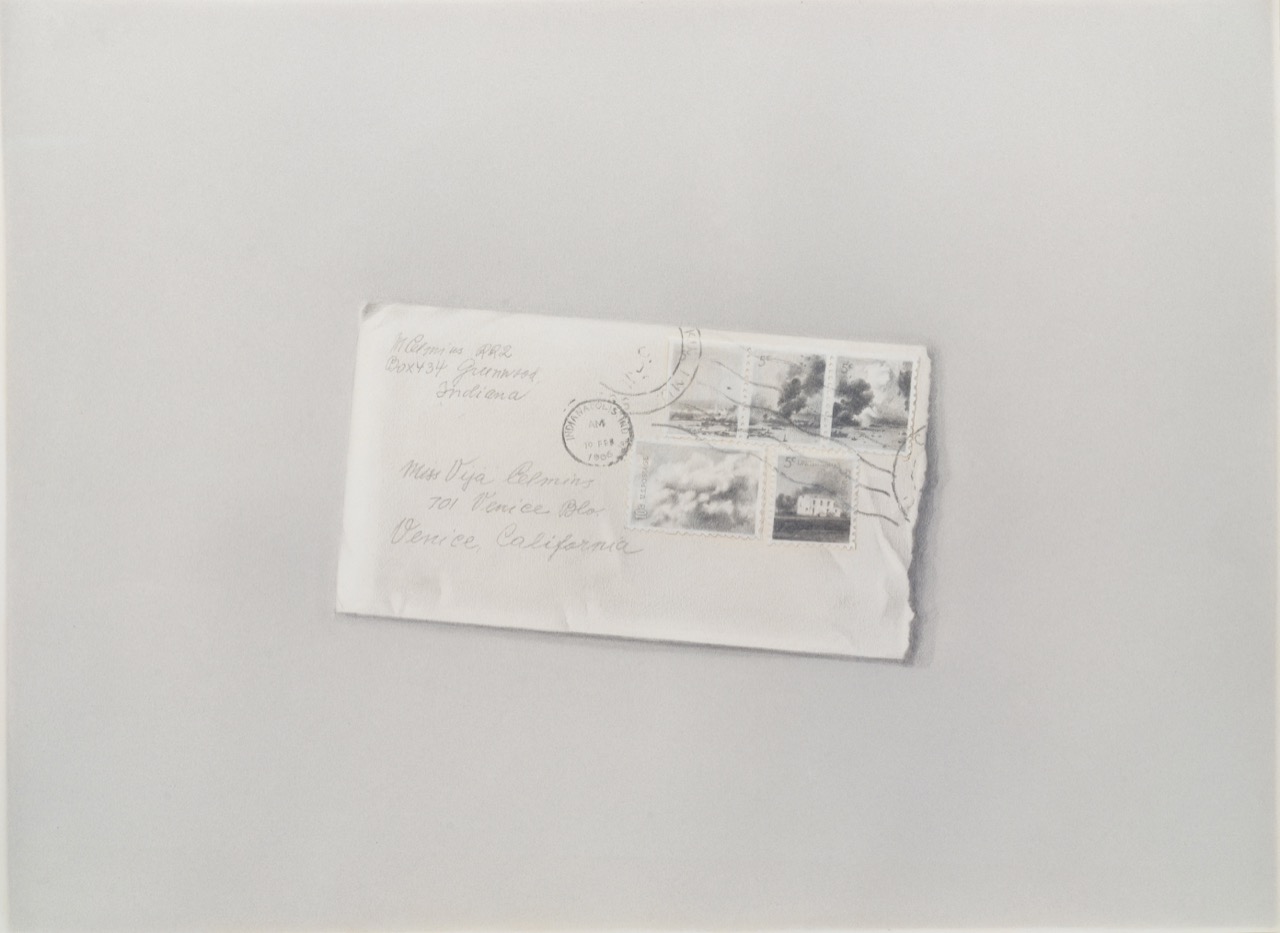

After a few years of painting, Celmins turned to drawing. It wasn’t simply a case of trying new things: she didn’t touch oils for well over a decade. The switch has the quality of a strike, a protest against pleasure. Celmins’s work shrank in scale but grew in weight: she crafted representations of disasters of war on small sheets of paper, all rendered in a steely graphite. American bombers, German planes, and Hiroshima offered subjects. Celmins, born in Riga, Latvia, in 1938, experienced the effects of World War II firsthand. War moved her west, and for a long time its imagery consumed her work, much of it made in the midst of the Vietnam War. A series from 1968, meticulous scale renderings of clipped or torn images resting on grisaille backgrounds (a zeppelin, a gun), has a mnemonic quality, but only one work alludes to the artist’s own dislocation. It depicts an envelope addressed to “Miss Vija Celmins, Venice, California.” The return address names Celmins’s mother in Indiana. Here we have a hereditary model, something passed down from mother to daughter, but the punctum—the connecting dot—lies in the stamps, things one touches with one’s tongue. Four picture billowing bomb sites at Pearl Harbor, the fifth a white clapboard house—bringing the war home. Celmins hand perforated each, pasting the miniature drawings onto the trompe l’oeil envelope. It might be the world’s most poignant collage.

Vija Celmins, Letter, 1968. Collage and graphite on acrylic ground on paper, 13 1/4 × 18 1/8 inches. © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Jason Mandella.

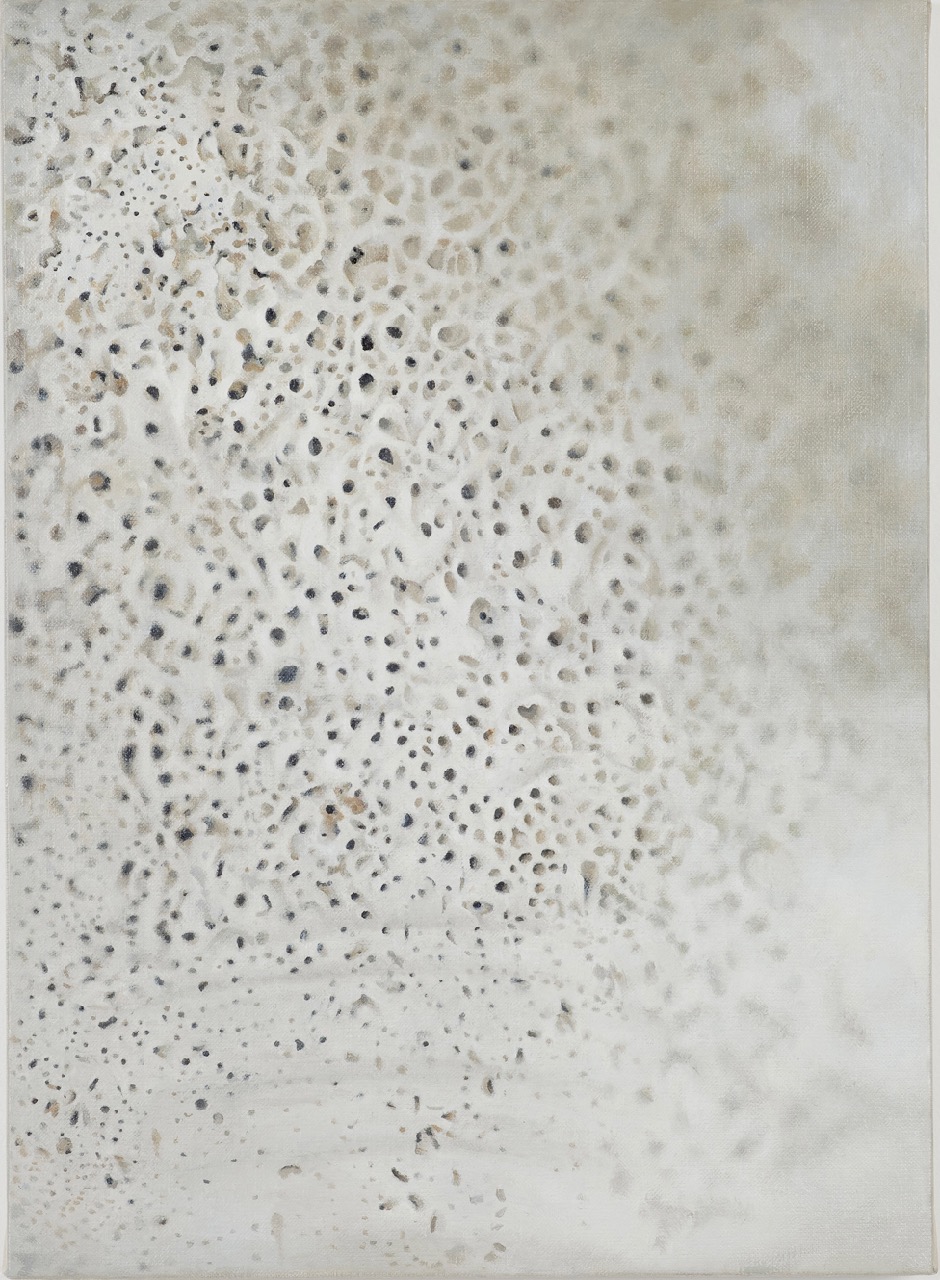

There is trauma in Celmins’s early work, then, but at the Met Breuer it is tucked away on the museum’s fifth floor, which feels like a haunted attic. On the fourth floor, a wide lofty space, the ceilings are high and natural light drives in from the windows. Here are the images for which Celmins is best known: even-keeled drawings of waves and webs, desert floors, stars pointilizing the sky. A man landed on the moon in 1969, and Celmins covered that, too. (These are some of the artist’s most fascinating works, their surfaces created from images of layered photographs. The artist’s other drawings are marked by a striking consistency, even anonymity, their scattered surfaces designed to resist any one point of focus.)

Vija Celmins, Untitled (Moon Surface #1), 1969. Graphite on acrylic ground on paper, 14 1⁄4 × 18 inches. © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Brian Forrest.

From this time on Celmins labored almost exclusively in series, and part of the pleasure of seeing her oeuvre together is to compare and contrast, to measure swells and crests against one another. Are these drawings metaphors? Or are they simply what they appear to be—slanted, stippled surfaces; studies in opacity? For Freud, “oceanic feelings” carried a quality of togetherness and wholeness, a connection between things. In Celmins’s hands, however, they are flinty and obsidian, more shell than liquid. The oceanic was a wellspring for modern art. Jackson Pollock’s 1947 painting Full Fathom Five found its title from a line in Shakespeare’s The Tempest: its thickened web of darkened lines conjure great depths. Celmins’s surfaces, on the other hand, ward off the deep: they ask us to meditate on and study exteriors. Her works are scholar’s rocks (and, not coincidentally, the artist’s stone sculptures are on display, too). Less meant for exhibition than contemplation, they belong to a tradition of slow seeing. One wants to look at them again and again.

Vija Celmins, To Fix the Image in Memory I–XI, 1977–82. Eleven stones and eleven made objects (bronze and acrylic paint), dimensions variable. © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource.

Celmins often spends many years on a single composition; she makes her images just right. In the mid-1980s she returned to painting, making new waves and inky night skies; later she embarked on a series of blackboards that channel the draconian power of education. All along she has also made prints, where she allows herself to indulge in juxtaposition (one shows a fighter plane next to a swath of black sky alongside a contraption by Duchamp). Off and on she has made sculptures, too. They stick out. Between 1977 and 1982, she created a magnum opus, To Fix the Image in Memory I–XI, replicas of eleven desert rocks paired with their models—things playing an old game of real and representation. The work lends the exhibition its title, and it seems to speak to the central tenet of her practice: Celmins is nothing if not a fixer. Image, too, is key. But I trip over the idea of memory. The title suggests that the artist is trying to install an image in her mind, or in the viewer’s. Perhaps she is. But there are involuntary memories and ones we make ourselves. The memories Celmins showed us in her first works seem to be in some sense what she has tried to dispel ever since. They were intentional, too, but different in nature from her later series: at a certain point the endless oceans and starry nights begin to feel like attempts to blanket over, or wash away, some painful idea. Perhaps timelessness is only an anxiety about time, but Celmins seems to have mastered it all the same.

Vija Celmins, Shell, 2009–10. Oil on canvas, 18 × 13 inches. © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery.

While the show has a first painting, it doesn’t possess a clear end. In Celmins’s most recent works she has examined the book cover of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (2008–10), as well as the texture of a shell (2009–10), but she hasn’t settled on a motif as certain as the desert or sea. She, like us, is circling around beginnings and conclusions, origins and remnants of life. The end, when it comes, will be captured not with a bang or a whimper, it seems, but with a cold, clear eye.

Alex Kitnick, Brant Family Fellow in Contemporary Arts at Bard College, is an art historian and critic based in New York. His writing has appeared in publications ranging from October to May.