Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Unexpectedly political innovations underpin the artist’s

decorative paintings.

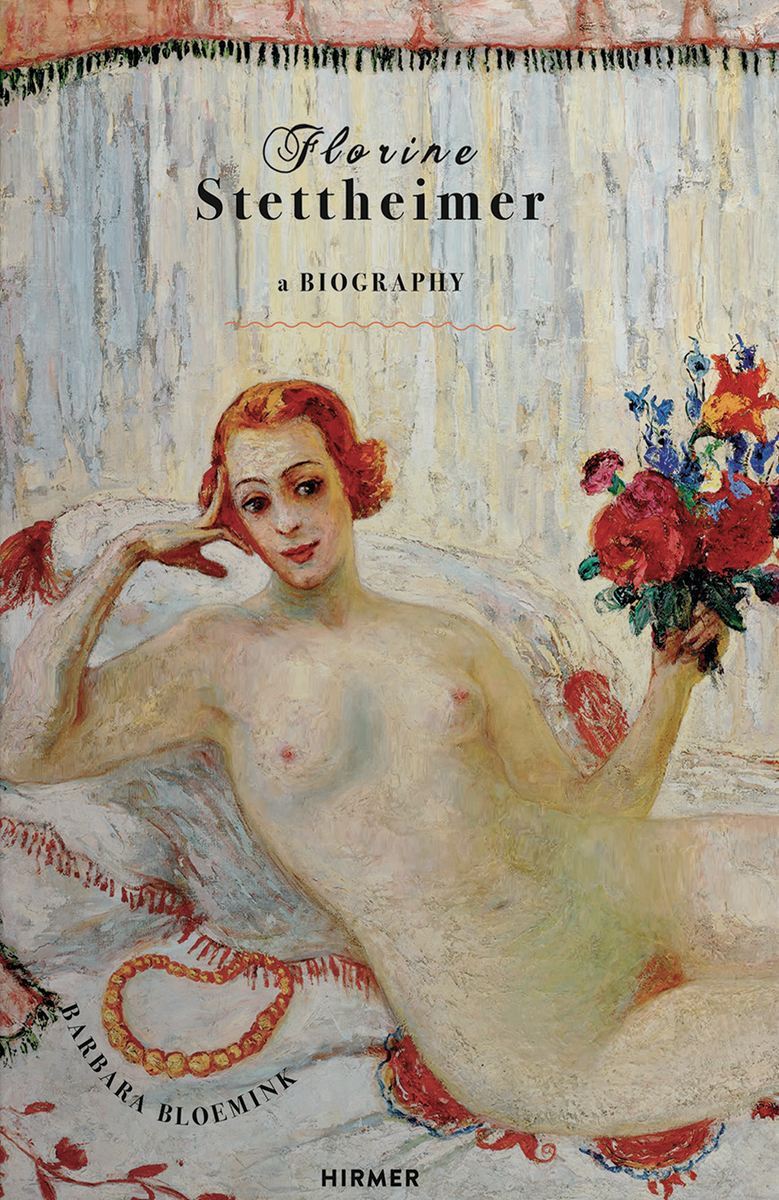

Florine Stettheimer: A Biography, by Barbara Bloemink,

Hirmer, 435 pages, $29.95

• • •

Writing in 1932 about the Whitney Museum’s First Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting the critic Henry McBride singled out Florine Stettheimer’s canvas Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue, from the previous year, as “the most modern in method” of the works on view. In it, Manhattan’s fabled thoroughfare of Gilded Age mansions, luxury shops, and the recently completed St. Patrick’s Cathedral is rendered in a scene of compressed geography and impossible simultaneity. With the panoramic scope of Bruegel and the airy delirium of Redon, Stettheimer captures a world bustling with activity, suspending it in meringue-like drifts of sidewalk and sky. And in a signature flourish, the artist depicts herself in the crowd. As a newlywed couple descends the composition’s central staircase, the unmarried Stettheimer has emerged—one in a trio of tiny figures that includes her likewise single sisters Carrie and Ettie—from a limousine in the bottom right. “It is cinematic, historic, fantastic, realistic, mocking, affectionate, calligraphic, encyclopedic, Proustian, and even portentous,” McBride rhapsodizes about the picture. “In fact, it has everything and everything in proportion.”

Florine Stettheimer, Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue, 1931. Courtesy Hirmer and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

For Barbara Bloemink, author of the already indispensable, fascinating new book Florine Stettheimer: A Biography (and co-curator, with Elisabeth Sussman, of the artist’s 1995 exhibition Manhattan Fantastica, also at the Whitney), McBride seems to serve—at least in her quotation of him here—as a kind of unrestrained alter ego. The tone of her text may be more measured and scholarly, but she argues just as passionately, in her own way, that her subject’s complex art embodies each of the attributes he lists—and she is just as confident as McBride in Stettheimer’s importance as a quintessentially modern artist.

Bloemink brings her account to life using a wealth of archival material from Stettheimer’s world (including letters from Marcel Duchamp, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz, and many more), as well as Ettie’s writings, and the artist’s diaries. From this last category, the biographer reproduces a generous number of Stettheimer’s brutally observant, beautifully terse, often very funny poems, such as this telling (undated) one:

Sweet little Miss Mouse

Wanted her own house

So she married Mr. Mole

And only got a hole.

Born to wealthy Jewish parents in 1871, in New York, the artist was raised mostly in Europe. Following her father’s desertion in 1878, her mother, Rosetta, moved Florine and her four siblings to Stuttgart. The family temporarily returned to New York in the 1890s—Florine attended the Art Students League and the younger Ettie enrolled at Barnard—before continuing their educations abroad. After years of extensive travel, the outbreak of WWI in 1914 precipitated their permanent relocation to the US. The elder siblings, Walter and Stella, married and moved to California; Rosetta and her three youngest daughters (by now in their late thirties and early forties) established a colorful household on the Upper West Side. They soon became legend as talented hostesses and salonnières. Known for their sophisticated interests, fashion sense, and open acceptance of varied sexualities, the women entertained—with singular flamboyance—an avant-garde cast of European émigrés and Americans at their Manhattan apartment and rented vacation homes in Tarrytown or Sea Bright. Stettheimer also famously gathered friends at her exquisitely furnished studio to unveil new works.

Florine Stettheimer, Spring Sale at Bendel’s, 1921. Courtesy Hirmer and Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Because her paintings resemble nothing else, and because she lived an unconventional life, there’s a tendency to consider Stettheimer as (merely) an eccentric, and to mistake the stridently decorative (one might say feminine) quality of her work for, if not frivolity or hobbyism, a cultivated obliviousness, reclusiveness, or outsider stance. Bloemink counters a number of myths and misconceptions (many of them originating in a fanciful 1963 biography by film critic Parker Tyler), seeing in Stettheimer’s mature style an insider’s calculated rejection of prevailing modes of both figuration and abstraction—as well as a stunning abandonment of the concerns of painting as a discrete medium—in favor of the experiential ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk. Noting the artist’s ecstatic reception, as a young woman in Paris, of a performance by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes—the profound impression left by its radical elevation of the applied arts through its innovative set and costume design—Bloemink explains that Stettheimer’s large-scale paintings were conceived of as “captured moments of theatrical productions.” Beginning in 1917 or so, “figures animate the space, caught in the midst of moving and gesturing,” the author writes. “Pure colors, often directly out of the tube, reflect emotional moods and ambient temperatures, while images of instruments and musicians imply sounds.”

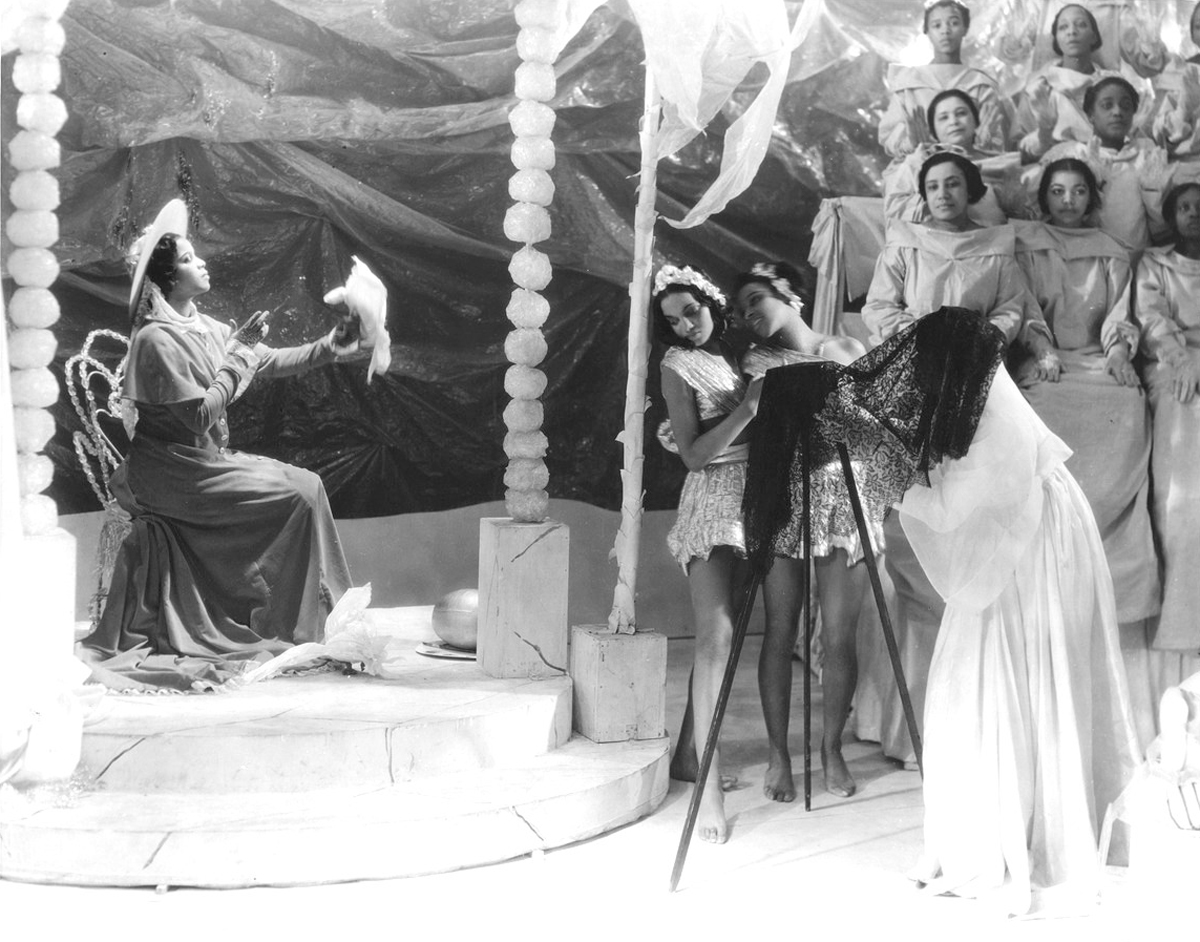

Francis Joseph Bruguiere, Six Scenes from Four Saints in Three Acts Opera. Courtesy Hirmer and the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Stettheimer’s collaboration, in the mid-thirties, with Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein on the opera Four Saints in Three Acts—an astonishing undertaking, the first of its kind to star all Black singers—was thus a culmination of a long-held dream. Bloemink’s detailed account of the artist’s creation of the costumes and stage set (an otherworldly, critically lauded, three-dimensional translation of her painting style) and her exacting, or obsessive, supervision of the production, gives perhaps the clearest view of Stettheimer’s vision and temperament. The behind-the-scenes blow-by-blow of the Gesamtkunstwerk’s evolution is also a window onto the class- and culture-bound, hit-or-miss radicalism of the period’s white avant-garde, in which a combination of wildly racist notions and forward-thinking experiments produced almost inexplicable endeavors, with very mixed results.

That said, through a sensitive chronology of Stettheimer’s life and enthralling, illuminating formal and symbolic decryptions of her paintings, Bloemink recasts Stettheimer’s perceived peculiarities as a fully formed, if cagey, kind of politics, and her work’s content as more explicitly progressive than I—and maybe other Stettheimer fans—had previously understood. The discussion of three paintings dealing with racism does not unearth new information, but their triangulation generates nuance; Stettheimer had a painterly knack for sugary or murmured satire that she used for social (and perhaps even self-) critique.

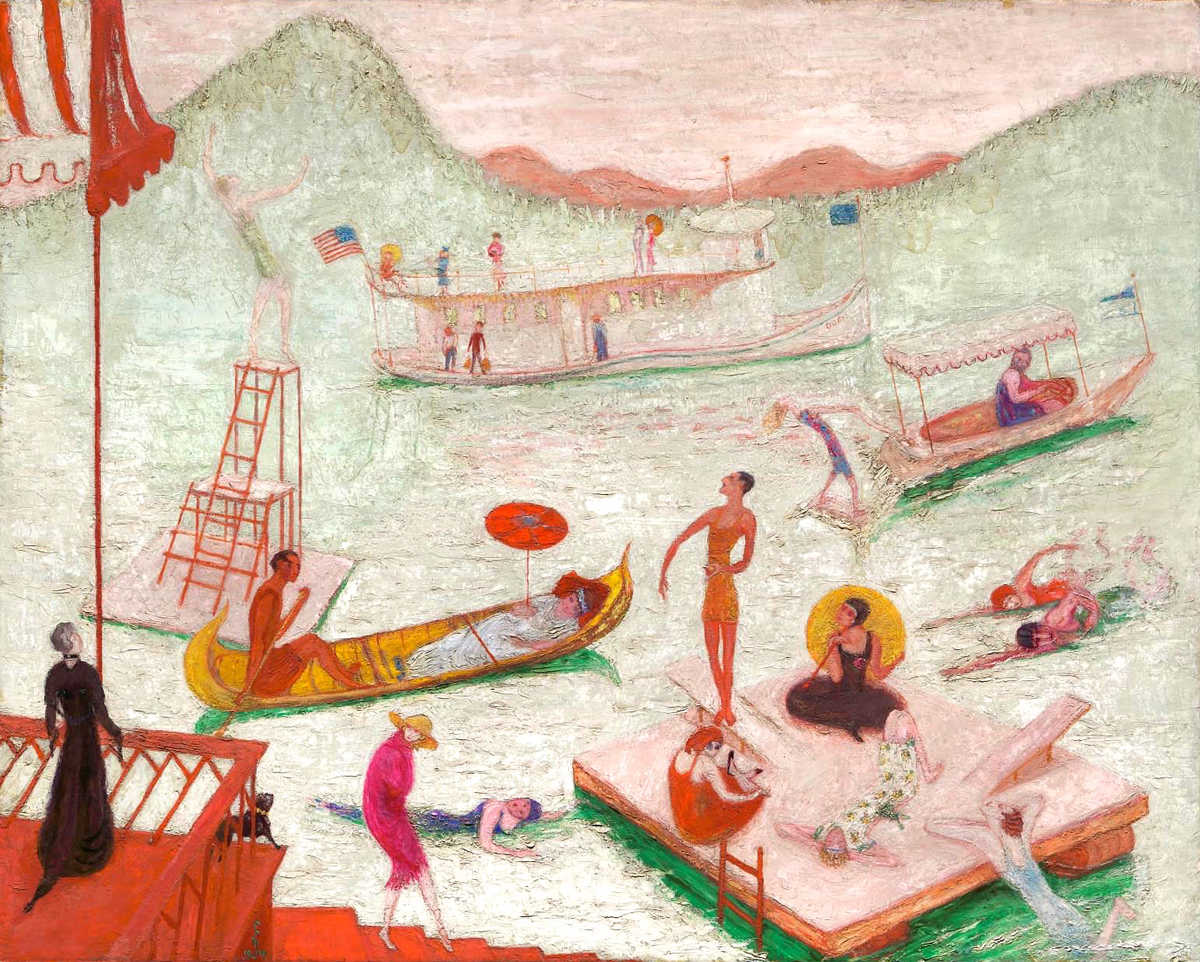

Florine Stettheimer, Lake Placid, 1919. Courtesy Hirmer and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The artist’s deceptively placid Lake Placid (1919) depicts Stettheimer and her family—and other Jews, as well as Catholics—swimming, boating, and lounging in a WASP-dominated vacation area whose prestigious club was notorious for its anti-Semitic policies. With the similarly composed Asbury Park South (1920), Stettheimer shows the Black stretch of beach in the then-segregated Asbury Park—a second scene of leisure echoing the first—and a group of her white friends visiting. It’s notable that Stettheimer, as a white American artist, has not caricatured the figures strolling on the boardwalk or relaxing on the beach—Black people are not literally or uniformly painted black, for example—and has made transparent a white observer’s (or interloper’s) point of view. (As Bloemink explains, “Stettheimer was not painting a depiction of how Black and white people interacted equally.”) In contrast, Beauty Contest: To the Memory of P.T. Barnum (1924) does portray Black musicians in an interchangeable manner, but the alarming (though almost unnoticeable) pattern on the gown worn by the pageant’s winner—a field of swastikas—suggests Stettheimer had twin attunements to American racism and the rise of the Right in Germany, as a European Jew.

Florine Stettheimer, Asbury Park South, 1920. Courtesy Hirmer and the collection of Halley K. Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld.

Reading Bloemink’s expert interpretations, paintings familiar to me—like the 1915 nude self-portrait that adorns the book’s jacket, or Stettheimer’s winking updates to the fête-galante genre—take on fresh, or more pointed, significance. If I had discerned in the past an amused disdain for high-society ostentation in Stettheimer’s depiction of the nuptials, center-stage in Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue (“Tiffany’s” is spelled out with jewels in the heavens above), I had somehow missed the significance of the composition’s bold white void: a spectral bride with fuzzed-out features holding a funereal bouquet of drooping calla lilies. It’s a reminder that, to Stettheimer, marriage was not simply unnecessary—it was a ritual of female obliteration or death. Maybe this is the unspecified “portent” that McBride hinted at, and nine decades later Bloemink can at last make perfectly clear.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.