Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

“As alone and as weird as possible”: a reissue of the composer’s

Automatic Writing.

Automatic Writing, by Robert Ashley, Lovely Music

• • •

Robert Ashley’s 1979 album, Automatic Writing, was reissued in December by Lovely Music, the label Mimi Johnson started in 1978 so she could put out records like Automatic Writing. It is such good news that this album is back and that Lovely is still here. Automatic Writing is the least audible album I love.

It is silvery and squished and unsettled. It susurrates and confuses and slips under its own door. I am not sure what to call it—filtered speech, circuit under sea, Bakelite ASMR ancestor, Al Green under pillow, mixing-desk puzzlement, brain under glass.

Automatic Writing announces its subject as difficulty, misunderstanding, and sadness.

It wouldn’t hurt to put the album on. What you hear, even when you turn it up, is violently soft. What exactly are you hearing? Words, spoken in clumps and drastically filtered. A metallic dribble that could be keys dragged across milk bottles. A church organ, playing across the street. A pop record buried under a hundred blankets. Lots of dead air. A woman speaking French. Forty-six minutes, unbroken.

You won’t hear the words as words, not for a while, but they are the why of the piece. Ashley described them in a talk he gave at the Walker Art Center in 1979, “The Meanings of Modernism”: “With regard to Automatic Writing and its origins, I had noticed that under certain specific situations of psychological or social stress—when there were too many people around me and I was reacting to too many obligations—I would tend to hide in the toilet. That is, I would go to the toilet more often than usual and while I was there I would tell myself stories. Just short stories. Not literary ‘short stories,’ but short (or not very long) stories, and inevitably a certain phrase would crop up in the telling.”

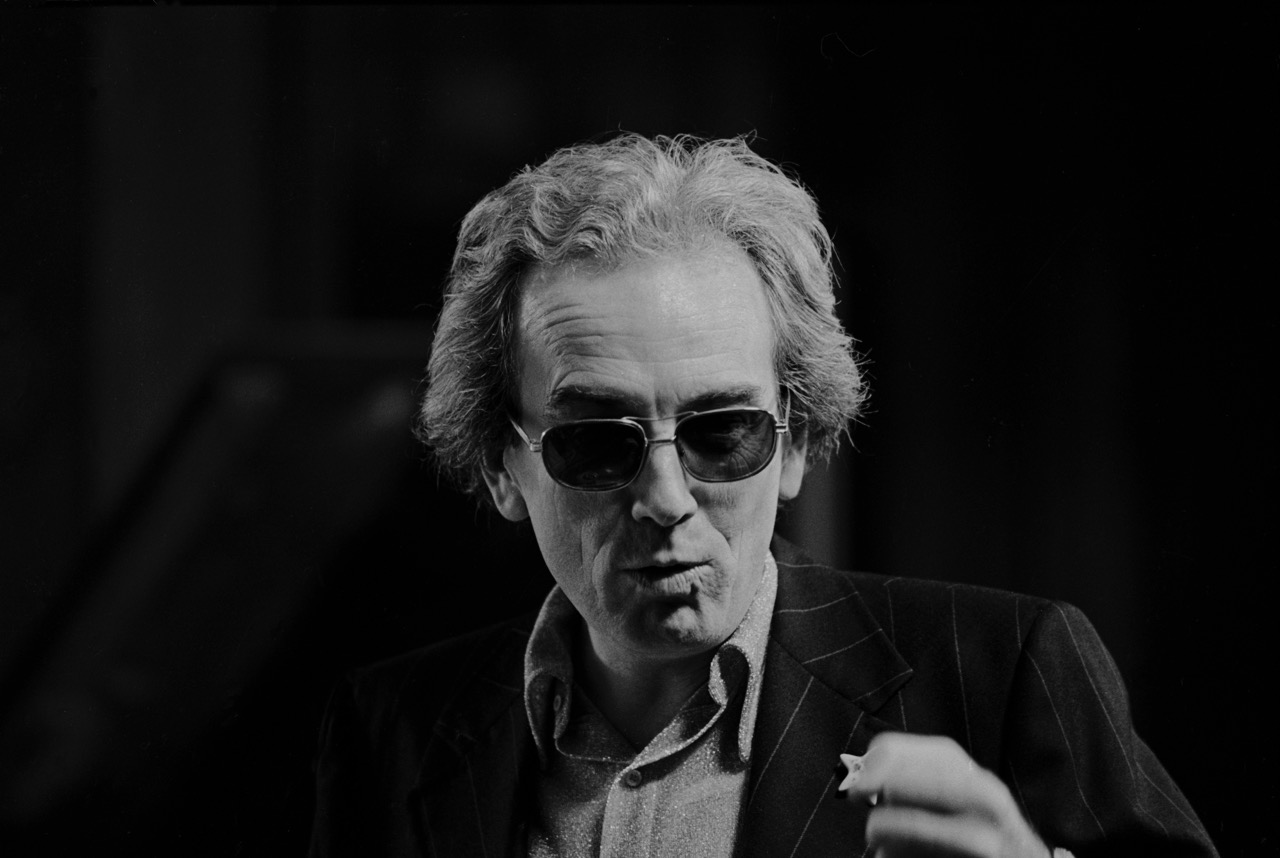

Robert Ashley, October 1975. Photo: Pat Kelly. Image courtesy Lovely Music.

In 1973 or 1974, Ashley started doing live performances of these phrases, routing the sound of his amplified voice through a simple but powerful circuit called a dual coincidence-switcher. “This magic box was invaluable to me for years,” Ashley said in 1999. The device was built for him in 1972 by electric media artist Paul DeMarinis and was central to the operation of three pieces: Automatic Writing, String Quartet Describing the Motions of Large Real Bodies (1972), and How Can I Tell the Difference? (1974). That weirdest of the weird sounds, the metallic pops, is Ashley’s voice being split into a sound that then splits itself.

In the summer of 1975, Ashley recorded his vocal track at the Center for Contemporary Music studio at Mills College. “All he did in the studio was record his own voice and attempt to be as alone and as weird as possible, as by himself as possible,” Lovely Music’s Johnson told me.

“The microphone was probably not more than an inch from my mouth,” Ashley said to electronic-music historian Thom Holmes in 1982. “It was about as close as it could be. That was the core of the piece, that sound of the close miking.”

In the final, commercially released version of Automatic Writing, the phrases Ashley repeats are “the Varispeed,” “you guys are all,” “fuckin’ clever,” and “I wanted to,” each of them four syllables. These are not the only words you hear, though—Johnson recites the French translation of Ashley’s words, and hers is the album’s clearest voice. The lyric sheet lists many Ashley fragments I’ve never made out, though I do like the idea of listening to Automatic Writing so patiently that I finally hear him say “things are really poppin’ on this second side.”

The idea that Automatic Writing has a lyric sheet is astonishing. When I started talking to the people involved, I expected someone to say, “What are you talking about? Nobody made that album.”

“I had the monologue itself with the electronics,” Ashley told Holmes. “I had the synthesizer accompaniment to that, the inversion of that. I had the sound of the French language. Then, I realized that I just needed a fourth character and finally I found it in that Polymoog part. So, those four characters had been performed in various different manifestations for a couple of years before I did the record. Then when I did the record the piece was over and I never wanted to perform it after that. I had finished it—I had found the four characters.” When Ashley says Polymoog, he means the organ sound; and the synthesizer “inversion” of the monologue is his speech put through the dual coincidence-switcher.

Robert Ashley, June 1976. Photo: Pat Kelly. Image courtesy Lovely Music.

Ashley didn’t tell Holmes about the Al Green album, Let’s Stay Together, that plays throughout, heavily suppressed. Johnson confirmed its use. “Yes, it is an Al Green record. He would have mixed that in because at the time he was living in what he called ‘the sordid apartment’ in Oakland, California. It was near Mills College and the guy downstairs played Al Green.”

Ashley mentions this in his 1994 opera, Foreign Experiences, in act 1, between lines 193 and 198:

Middle aged man lives alone in a shit apartment

Across the courtyard a woman with an artificial larynx

Down below the neighbor has a bar self-standing

And he plays disco records / until late hours

Donna Summer and Al Green without the words

Just strong beats end of scene six.

What could be more Robert Ashley than entombing another record inside his own? Once a sound-recording engineer for commercial films, Ashley was as interested in the possibilities of audio as he was in the rhythms of American English. Automatic Writing is an interaction that could only exist in recorded space, a comment on space itself as rendered through speech. It is an oblique chapter in the history of Ashley’s career as his own voiceover artist.

Automatic Writing is an attempt to help the suffering body, to rescue someone who isn’t going to make it, to help a wobbling soul who, against advice, has been taken to a recording studio, to find life as a copy, somebody strong, stronger than a weaker signal but only an echo of the person-signal, the smallest sound broadcast into a room, bounced off the wall, gathered up, strained through cheesecloth, and printed straight to tape.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.