James Hannaham

James Hannaham

Blackness and blankness in the artist’s first solo show.

Aria Dean, Baby is a Cool Machine, installation view. Photo: Stan Narten. Image courtesy the artist and American Medium.

Aria Dean, Baby Is a Cool Machine, American Medium, 515 West Twentieth Street, New York City, through November 25, 2017

• • •

Two years ago, Aria Dean graduated from Oberlin College and became social media coordinator for the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. Last year, she began a new position as an assistant curator for Rhizome at the New Museum. Yet this rising art star and social media maven had still more facets to flash at us. She has opened her first solo show, Baby Is a Cool Machine, at American Medium in Chelsea. According to her biography, she has written for Artforum and Art in America, among other publications, and given lectures at the New Museum and UCLA. Her Oberlin degree, by the way, is a BA. She’s twenty-four. Baby is indeed a cool machine.

Based on Dean’s youth, one is tempted to drag out stock phrases like enfant terrible or wünderkind, but when I visited the gallery and first encountered her work, I did not know her age, which is why I feel it worth reporting at all. Her sensibility comes off so self-assured and understated that it oozes maturity—I could’ve sworn I had just discovered a seasoned artist who had flown under the radar for a while.

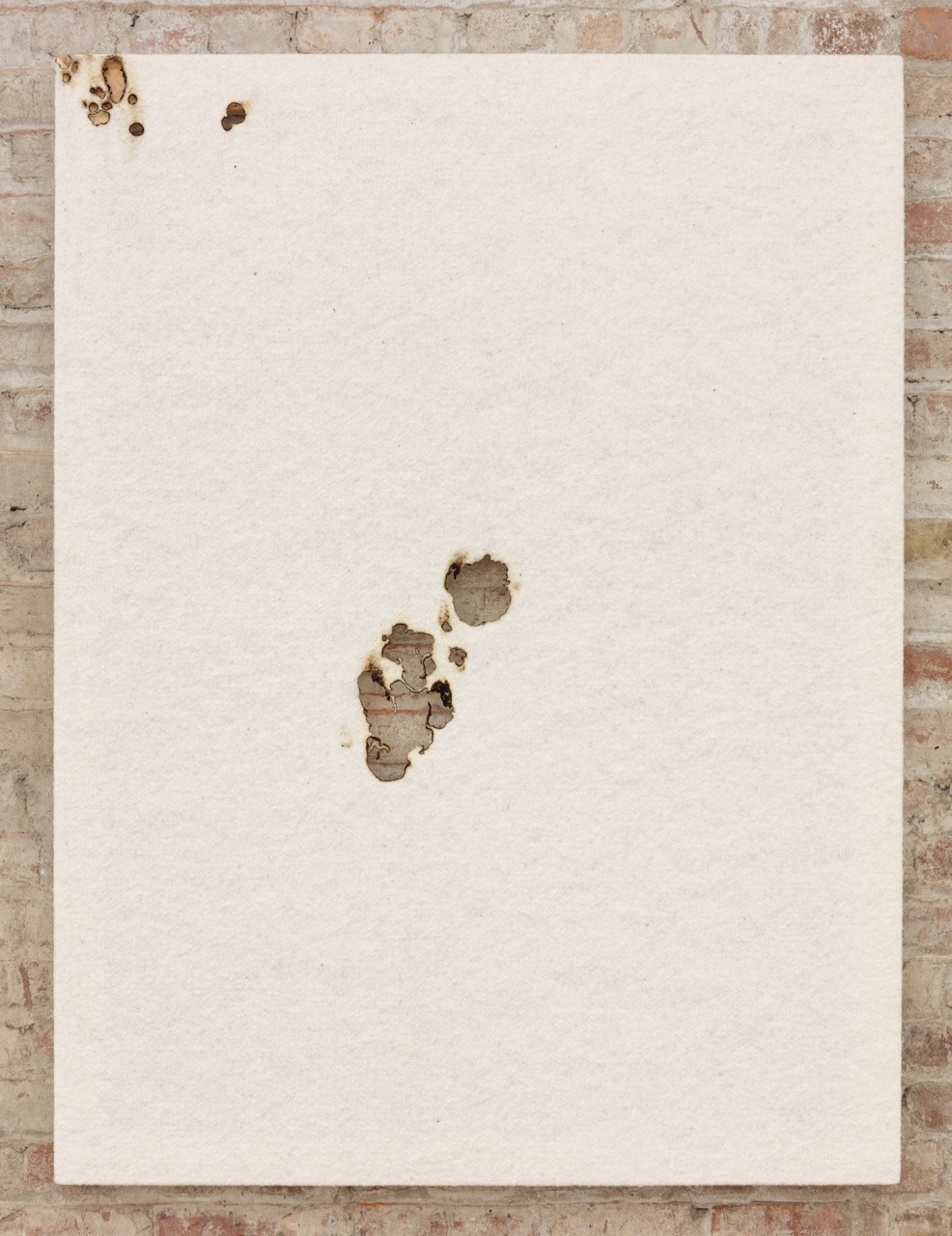

Aria Dean, Untitled (Canvas #1), 2017. Cotton batting, stretcher bars, 48 × 36 inches. Photo: Stan Narten. Image courtesy the artist and American Medium.

The show consists of seven more-or-less conceptual pieces in various media, as well as a video. Four of the seven are rectangular constructions that hang in different spots on the brick walls of the gallery. Paintings? Not exactly—cotton pulled tightly across stretcher bars, and in some of the pieces, strategically burned. What is that on the floor? A piece called Carry the Zero, consisting of a clear plastic thing that seems like a child-sized effigy or suit of some kind; it has a head, two arms, two legs, and a plastic tube that curls out of the neck. At first one thinks it could function as a transparent ghost costume or a beginner’s wet suit, but on closer inspection, the humanoid shape actually mimics one of those Ped Xing figures that appear on traffic signs. Elsewhere, a metal bar attached to the floor like a squared-off bike rack holds a giant red satin bow that hangs from a chain. Dean calls it Untitled (Obscenities). Blobs of wax have dripped on the bar, the bow, and on the place where the chain hooks up with it.

Aria Dean, Untitled (Obscenities), 2017. Galvanizing steel, silk, wax, chain, 39 × 50 × 10 inches. Photo: Stan Narten. Image courtesy the artist and American Medium.

These objects feel incredibly neutral and manufactured, enough so that I started to look with fresh eyes at the odd architectural details of the room—is that metal air duct along the baseboard part of the show? What about that conduit hanging off the wall? Did Dean put that brick-shaped hole in the wall with the greenish putty and the metal duct? Or the vaguely child-shaped discoloration in the concrete floor near Carry the Zero?

We’re encouraged by the gallery handout to consider Dean’s objects in terms of blackness (her blackness, of course) and autobiography (also hers). And indeed, one can make an easy leap from stretched burned cotton to a slavery reference, or even more facilely, from literal blackness to the construction BLACKBOX, a dark, twelve-inch by ten-inch by six-inch box shinily engraved on all sides with possibly random alphanumeric characters in what looks like a very long, very secure password. The video, A River Called Death, refers to both blackness and autobiography somewhat more directly than any of the other pieces. It consists of a single shot of Mississippi’s Yazoo River, with intermittent blackouts (black outs, perhaps?), and a series of subtitles outlining the various grim histories surrounding that fabled waterway, conjuring “the bodies on the floor, weighed down with bricks.” To paraphrase Langston Hughes, the Negro has been speaking of these same rivers in this way for quite some time.

Aria Dean, A River Called Death, 2017. HD video, 7 minutes, 33 seconds. Photo: Stan Narten. Image courtesy the artist and American Medium.

However, the autobiographical content of this piece is more oblique and sophisticated than meets the eye. Dean’s from California; her grandfather and his brother had to flee Mississippi because, her gallery tells me, of “an incident with a white woman.” (As far as I know, accusations of rape followed by lynchings were pretty much the only incidents with white women available to black men in Mississippi during that era that required them to skip town.) Generously, Dean has chosen not to mine her own personal drama, but a larger, more collective type of trauma, beginning with difficulties faced by previous generations that shaped her life profoundly, and nodding toward the scars of history.

Aria Dean, Carry the Zero, 2017. Vinyl, nozzle, 24 × 50 × 3 inches. Photo: Stan Narten. Image courtesy the artist and American Medium.

While one can quickly glean the relationship of some of Dean’s art to blackness and autobiography, it’s weirder and more powerful to imagine the connection to blackness and autobiography in a piece like Carry the Zero. Did all the blackness drain out of the Ped Xing silhouette? If so, where does this blackness go when it leaves? Does this transparent figure have some connection to a personal story about blackness from the artist’s childhood? Do we need to know that story in order to appreciate the work—or can we just wonder?

There’s a slippery quality to this piece, as well as to Obscenities, reminiscent of multimedia artist Ralph Lemon’s more deadpan explorations into blackness, and even blankness. Is wax dripped on as stereotypically feminine a symbol as a bow—a gigantic, almost fleshly bow—meant to suggest sadomasochistic roleplay of some kind? In what ways does blackness, or can blackness, align or misalign itself with the idea of S&M? And does the title refer to the scandalous intersection of all of these possibilities? Like Lemon, Dean knows that black art is whatever a black artist says is black art, and that others will tend to read work by black artists almost exclusively through the lens of race anyway.

She also knows that to make work devoid of investigations into race also constitutes a risk—that people (black people, likely at first) will give an artist a whole lot of grief if they don’t address blackness in their work in some legible way. Those with beef will often labor under the assumption that only a self-hating black artist would turn away from that subject matter. On top of that, black artists must also negotiate the questionable institutionalization of blackness by predominantly white establishments like the art world and academia. And yet, how to get by? How to get free? Dean, already so sagacious, has fearlessly begun to navigate those particular rivers called death.

James Hannaham has published a pair of novels: Delicious Foods, a PEN/Faulkner Award winner and New York Times Notable Book, and God Says No, a Lambda Book Award finalist. He practices many other types of writing, art, and performance, and teaches a few of them at the Pratt Institute.