Reinaldo Laddaga

Reinaldo Laddaga

More comedies of incongruity from the Scottish painter.

Peter Doig, installation view. Image © Peter Doig, courtesy Michael Werner Gallery.

Peter Doig, Michael Werner Gallery, 4 East Seventy-Seventh Street, New York City, through November 18, 2017

• • •

Visiting Peter Doig’s exhibition of new paintings at Michael Werner Gallery—comprising two monumental canvases and almost thirty smaller works—I was reminded of an essay by Jonas Mekas on the films of Andy Warhol. Mekas tells us that he has been reading “some old English texts,” the late medieval French epic La Chanson de Roland, and the German Vogelweide. “Oh, the beauty,” he says, “of the Old French, and the High German, and the Old English! Why is it so that languages seem to become slicker with time? They seem to lose those raw edges, that earth quality.” He goes on to explain that he finds this elusive quality in much underground American cinema, including Warhol’s. Unlike both Hollywood and European art film, it “has those raw edges, those mysterious areas where the imagination can roam, where we can erect our own under-textures and under-structures—those mysterious blanks, spaces, muddled noises which can be interpreted two, three, four, ten different ways.”

One also finds this “earth quality” in the work of Peter Doig, whose occasionally opulent pictures toy with poverty and failure, and whose propensity to the sublime is tempered by a passion for the banal. The resulting images are highly unstable: they look somehow not fully formed or seem to be in the process of dissolving. In this show, we are often left with the impression that the artist, faced with the task of materializing an image, has tried several strategies, attempted to settle in on one, and, not having been able to do it, left the work permanently unfinished. Different styles and techniques coexist in the same canvas (pencil sketches, zones of washed color, sudden details executed in lucid oil), and this variety seems particularly well suited to the comedies of incongruity that Doig’s work often enacts.

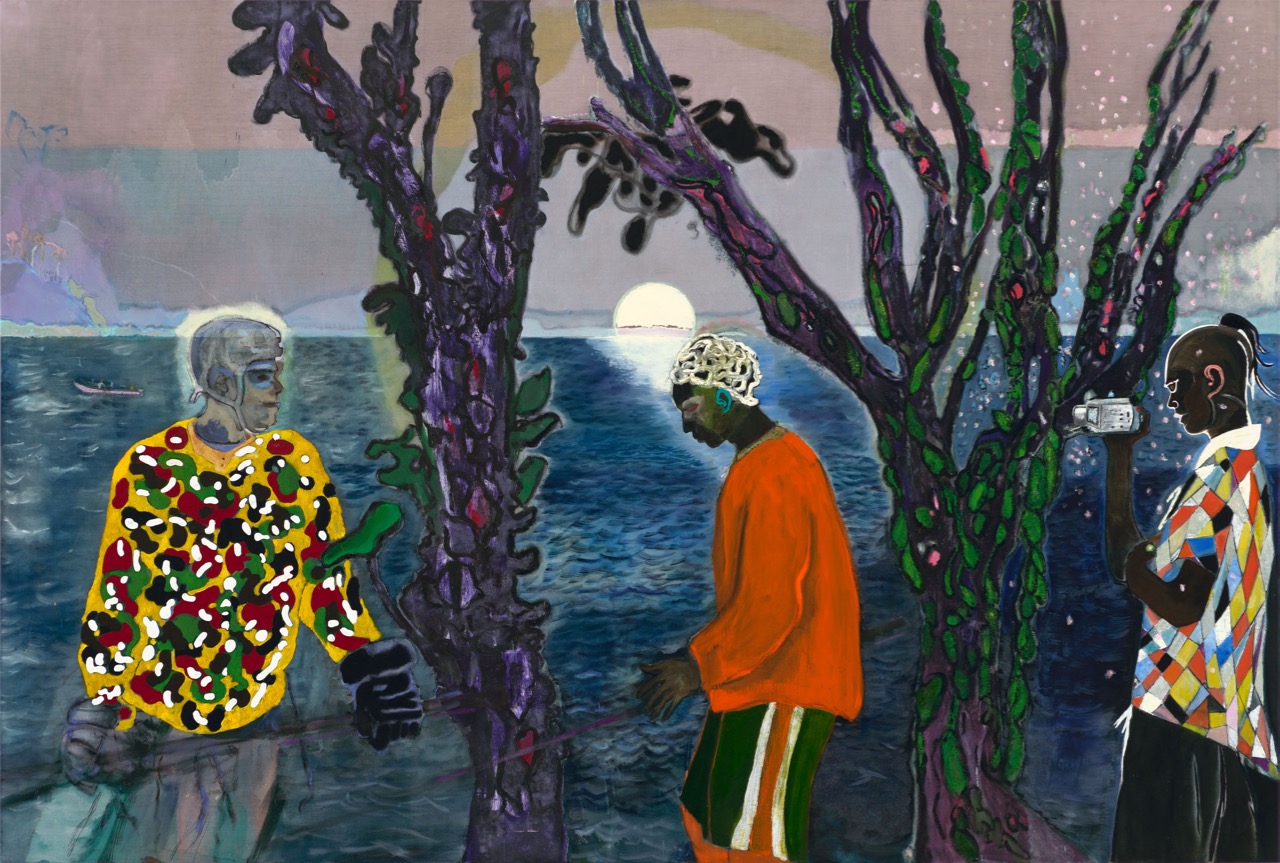

Peter Doig, Two Trees, 2017. Oil on linen, 94 ½ × 139 ¾ inches. Image © Peter Doig, courtesy Michael Werner Gallery.

Take Two Trees, one of the two large paintings that anchor the exhibit. Despite the title, our attention is caught less by the pair of green and violet forms erected in front of a mass of water over which the sun or the moon is rising or descending, than by three disparate figures who stand between them: a hockey player whose head is barely sketched but whose jersey is heavily impastoed with touches of yellow, green, and red; a man wearing a deep-orange jersey and a white, perhaps knitted, cap; and a harlequin-like figure holding a camera. These spectral characters have landed in the same space, but it is impossible to imagine an interaction between them. The hockey player and the man in the orange jersey might be playing a game (of what?), and the cameraman may be recording the game to show it later (to whom?). But it’s not clear if they are even aware of one another, and the nature of their activities remains undefined. The poet Derek Walcott has a wonderful line to describe Doig’s Gasthof zur Muldentalsperre from 2000–02, which contains two men waiting (we don’t know for what or whom) at the end of a walled path: a “sweet insipidity unites the two.” A common blandness, an identical air of barely-being-there, similarly unites the figures in Two Trees.

Peter Doig, Red Man (Sings Calypso), 2017. Oil on linen, 116 ¼ × 76 ¾ inches. Image © Peter Doig, courtesy Michael Werner Gallery.

Doig has said that he expects his images to be bathed in an atmosphere of “blankness,” “mutedness,” “numbness.” And blank is the expression of the main character in the show’s second large painting, Red Man (Sings Calypso). The work depicts a beachside scene centered on a young man in a brief swimsuit, proudly and precariously standing in front of a gargantuan lifeguard’s chair, clutching his hands and presumably singing calypso (although his mouth is closed). He is the obvious protagonist of the piece, but we can’t take our eyes off another quasi-naked figure: a blue man, ignored by the singer, who grabs a writhing snake with both hands—a Laocoön without his children in a tropical resort. But his expression has nothing of the agony and terror of the classical statue, and there’s something humorous about his appearance, his careful hairdo and elegant sunglasses. We soon realize that we don’t even know if man and reptile are fighting or playing, if the serpent is the man’s enemy or pet.

Peter Doig, installation view. Image © Peter Doig, courtesy Michael Werner Gallery.

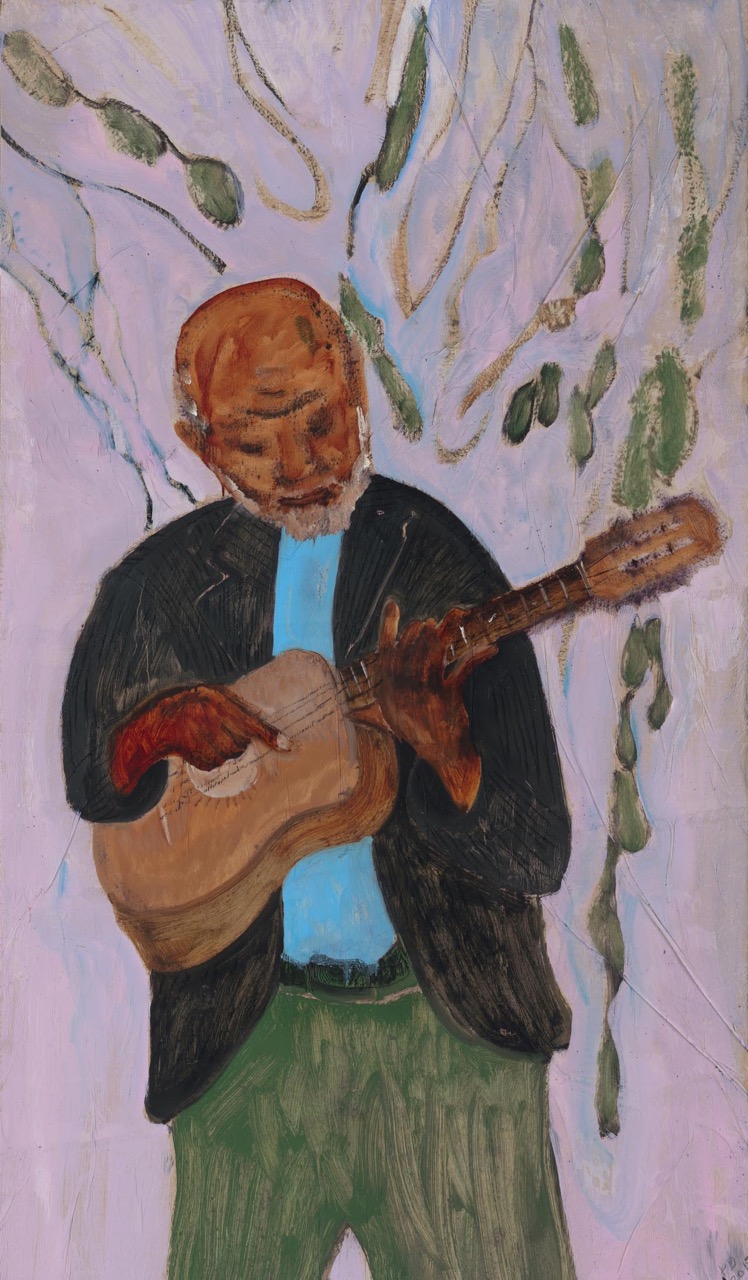

Surrounding the two large paintings and in a back gallery, one finds the smaller, more improvisatory paintings, hung salon style, their sizes ranging widely (from under ten inches to over five feet tall). Most are connected to pictures shown at Michael Werner two years ago via a series of recurring motifs: a lion ostentatiously legendary, a long yellow wall in the sunshine, a person walking or leaning on the wall. There are two portraits of Emheyo Bahabba (known as Embah), a Trinidadian painter who, until his recent death, had a studio next door to Doig’s in Port of Spain. A few are variations on the characters in Red Man (Sings Calypso). Some are so apparently insignificant, so tentative, so vague and desolate that their presence in the show is somewhat baffling. But taken together, the paintings on view convey the impression—borne by their provisional, unfinished appearance—that behind each image there is another image, behind each drawing another drawing, behind each composition another story. And, particularly in the large-scale canvases, each surface hides another surface, each stroke conceals another, so that they invite an observation that is somewhat archaeological: we are compelled to go beyond the surface, but are kept in the dark about what, if anything, might be there to see.

Peter Doig, Embah in Paris, 2017. Oil on vellum mounted on board, 61 ¾ × 35 inches. Image © Peter Doig, courtesy Michael Werner Gallery.

Years ago, when Doig painted mostly buildings hidden behind trees or characters screened by falling snow, he said that he wanted to “paint the strain on the eye of looking through to find focus . . . to get people to look right into the picture, to peer into it, almost like woods that are so thick that you have to keep on looking to see anything at all.” The description is also an apt one for the works in Doig’s current show. The strain of the eye and of the imagination, persisting until the mind goes mute and blank, but keeps pulsing and moving toward the images that face it, patiently working through its own numbness. In a world where our attention is relentlessly grabbed, shaken, and swayed by crooked streams of information, this is not such a bad place to make a stand.

Reinaldo Laddaga is a writer and critic who lives in New York. His latest book is Things That a Mutant Needs to Know: More Short and Amazing Stories, a collection of short stories and musical miniatures made in collaboration with eighteen composers. His website is www.rladdaga.net.