Tobi Haslett

Tobi Haslett

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s newly restored film tracks a Baudelaire of

Castro’s Cuba.

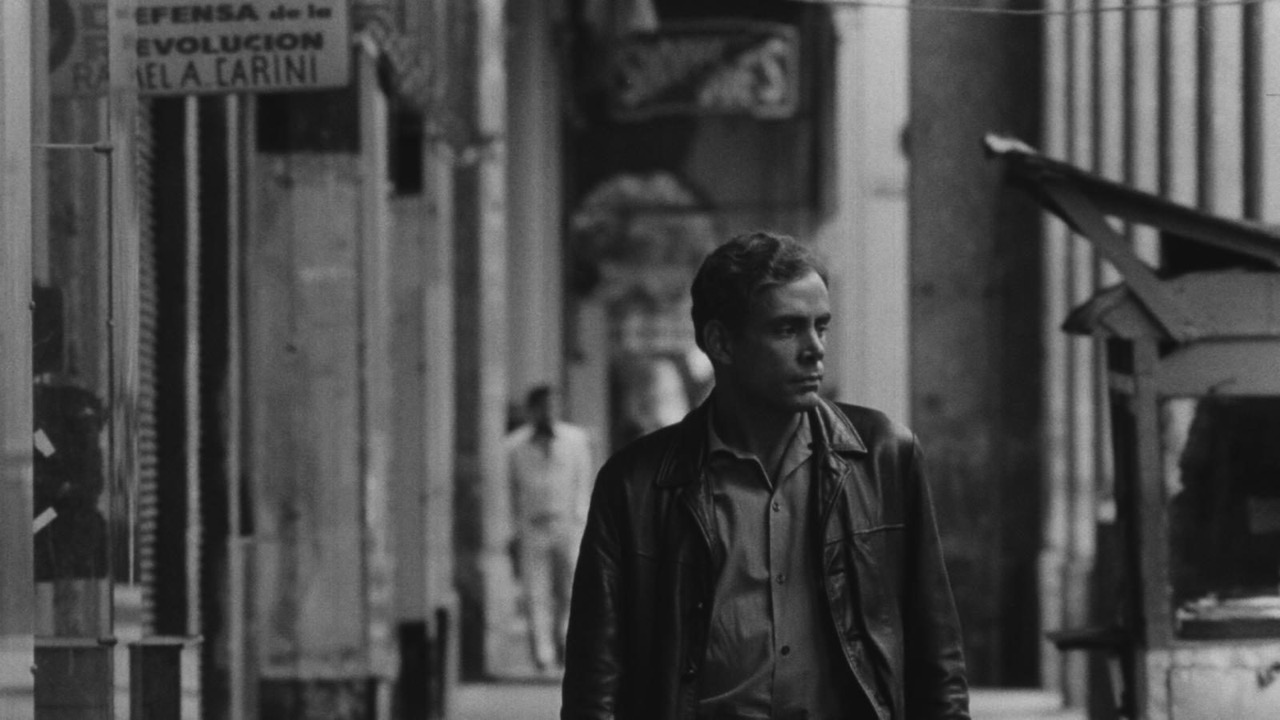

Sergio Corrieri (Sergio) in Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. Image courtesy Film Forum.

Memories of Underdevelopment, directed by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City, through

January 18, 2018

• • •

“Underdevelopment”: the word has a metallic impersonality, jingling at a technocratic distance from the lives it condemns. But it points to the brute and the fleshly—slums, guns, filth, famine, the little garland of clichés that adorn our vision of the Third World. Now, of course, we call it the “developing world”—a bit of optimism dribbled in to leaven the contempt.

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968), the fifth and most famous film by the Cuban director Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, is a wry survey of an underdeveloped city in an underdeveloped nation, a place both brightened and scrambled by socialist promise. The film’s hero is Sergio—played with gorgeous disdain by Sergio Corrieri—a debonair bourgeois who strides through post-revolutionary Havana, his Europhilia knotted ascot-like around his sophisticated sensibility. He had always wanted to be a writer—and now, in 1961, after the seizure of his father’s furniture shop, after the Bay of Pigs invasion, after the flight of his friends and family for the gleaming freedom of Miami, he finds himself ambling through his hopeful, dirty city, twirling his psyche like a cane. His days bristle with an elaborate agitation, as his amusement at the “new” Cuba collapses into bafflement and curdles into pique.

Sergio Corrieri (Sergio) in Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. Image courtesy Film Forum.

“All those who loved me and bugged me up until the last minute,” Sergio bangs on a typewriter near the film’s start, “have left.” So have his privileges. He reacts to this with smirking ambivalence and an urbane melancholia, at once contemptuous of the deposed Batista regime—its fascists and toadies and jackbooted torturers—and leery of his role in this roaring new world. He looks out at the city’s skyline from a telescope on his balcony, drinking in the whole dreary panorama of statues and smokestacks and gray little squares. “Nothing has changed,” he murmurs to himself. “Nothing has changed.”

Gutiérrez Alea’s film, which has been treated to a 4K restoration on the fiftieth anniversary of its premiere, is based on the novel by Cuban writer Edmundo Desnoes—which perhaps explains the link, in this brooding fable of modernization, to the dilapidated masculinity of literary modernism, with its glib, amoral heroes who drift through capitals and scorn all hope. The ghosts of Camus, Ionesco, and Joyce seem to rattle their chains—Sergio intrigues us like Meursault and blunders like Bloom—but Baudelaire is the writer evoked most pungently by our pretty, listless principal. Perhaps it’s the flashes of cruelty—his coldness to his family and fecklessness in love. Gutiérrez Alea could have called it Havana Spleen.

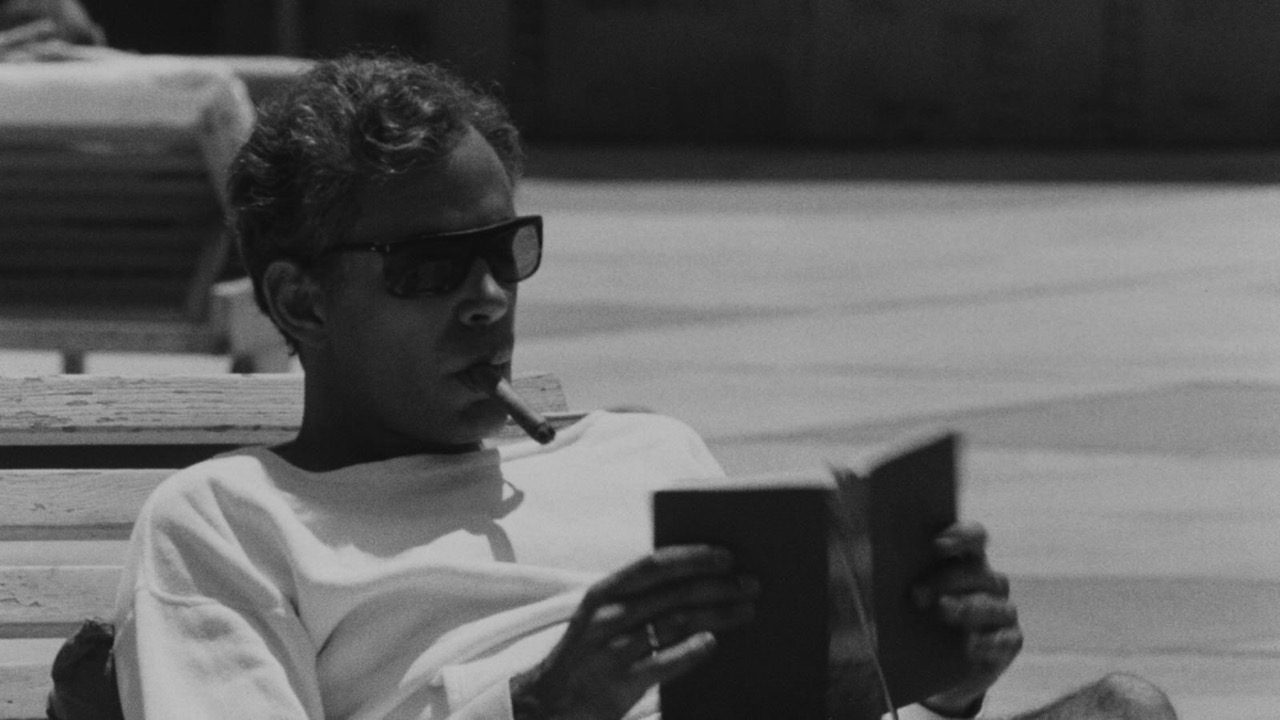

Daisy Granados (Elena) in Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. Image courtesy Film Forum.

But he didn’t. This is an ode, finally, to underdevelopment, to the brutish material forces that thrash and forge the self. The psyche, rather than a precious bauble of twinkling interiority, is seen to take dictation from its sociopolitical surround. “One of the signs of underdevelopment,” Sergio muses ruefully, is “an inability to establish links, to gather experience and grow.” He is referring to Elena (Daisy Granados), his young lover who dreams of being an actress. Their first meeting is taut with panting want; he sees her standing outside a building and spits a wolfish remark about her beautiful knees. It’s soon revealed that she is waiting to do a screen test with some men from the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC), the state-run production company that released films meant to pulse to the rhythm of socialist revolution.

Gutiérrez Alea himself was a founding member of ICAIC—and this film’s twitching preoccupation with the moving image is the source of its glinting, eloquent critique. Clips of Marilyn Monroe and Brigitte Bardot flash across the screen, glistening tokens of the capitalist world and its sensuous lures (though Monroe, of course, was in favor of Castro’s New Year revolution). And Elena’s girlish wish for big-time (Marxist) movie-stardom is a touching, wonky allegory for a new, perhaps vulgarized sense of national belonging—here are the People, freshly empowered and vibrating with optimism, pleading to be plastered over the massive silver screen. “Are you a revolutionary?” Elena asks Sergio, giggling.

Daisy Granados (Elena) in Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. Image courtesy Film Forum.

For all its stylish disaffection and New Wave chic, Memories of Underdevelopment stands as a righteous exemplar of “imperfect cinema,” a phrase coined by the Cuban filmmaker Julio García Espinosa in his famous manifesto from 1969. It’s a brisk, crackling document, swiveling furiously to inspect the material conditions and ideological attachments that foster and hinder a truly revolutionary cinema. An imperfect cinema wouldn’t simply mimic European or North American films—with their laminated smoothness and trite, preposterous themes—but would be shot through, broken brilliantly open, by historical responsibility and militant commitment. Hence Gutiérrez Alea’s deft use of documentary footage: Sergio’s glamorous monologues are curved and cut by economic and sociological data, as the cinema—that glimmering site of voluptuous spectacle—packs on the bulging muscles of revolutionary discipline. Here is a human life, with all its moods and whorls, doing its dialectical dance with the vastness of the collective. “Art will not disappear into nothingness,” read the vatic final lines of Espinosa’s manifesto. “It will disappear into everything.”

Sergio Corrieri (Sergio) in Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. Image courtesy Film Forum.

And everywhere. In 1973, Memories became the first Cuban film to be released in the United States after the start of the embargo—and was met with a distinct rumble of satisfaction from a First World audience pleased by what looked like a break with the Castro regime. “Different groups of spectators,” confessed Gutiérrez Alea in 1980, “may understand the content in diverse ways, according to the ideology prevalent in each group.” That he remained loyal to the revolution should be clear to anyone who isn’t raking through the film for damning proof of this perfidy or that disillusionment—especially since Sergio, for all of his alluring charm, isn’t exactly a sympathetic figure, but crude, cruel, stymied, weak, astonishingly passive and malevolently unmoored. Not, then, a political anchor for the film so much as its flapping bourgeois bat, emitting its call at some impossible pitch so it can find its way in the dark.

Tobi Haslett was born in New York. He has written about art, film, and literature for n+1, the New Yorker, Artforum, the Village Voice, and elsewhere. He is currently a doctoral student in English at Yale.