Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

Bridges, follies, towers: the Met Breuer hosts a career retrospective.

Siah Armajani: Follow This Line, installation view. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Siah Armajani: Follow This Line, the Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue, New York City, through June 2, 2019

• • •

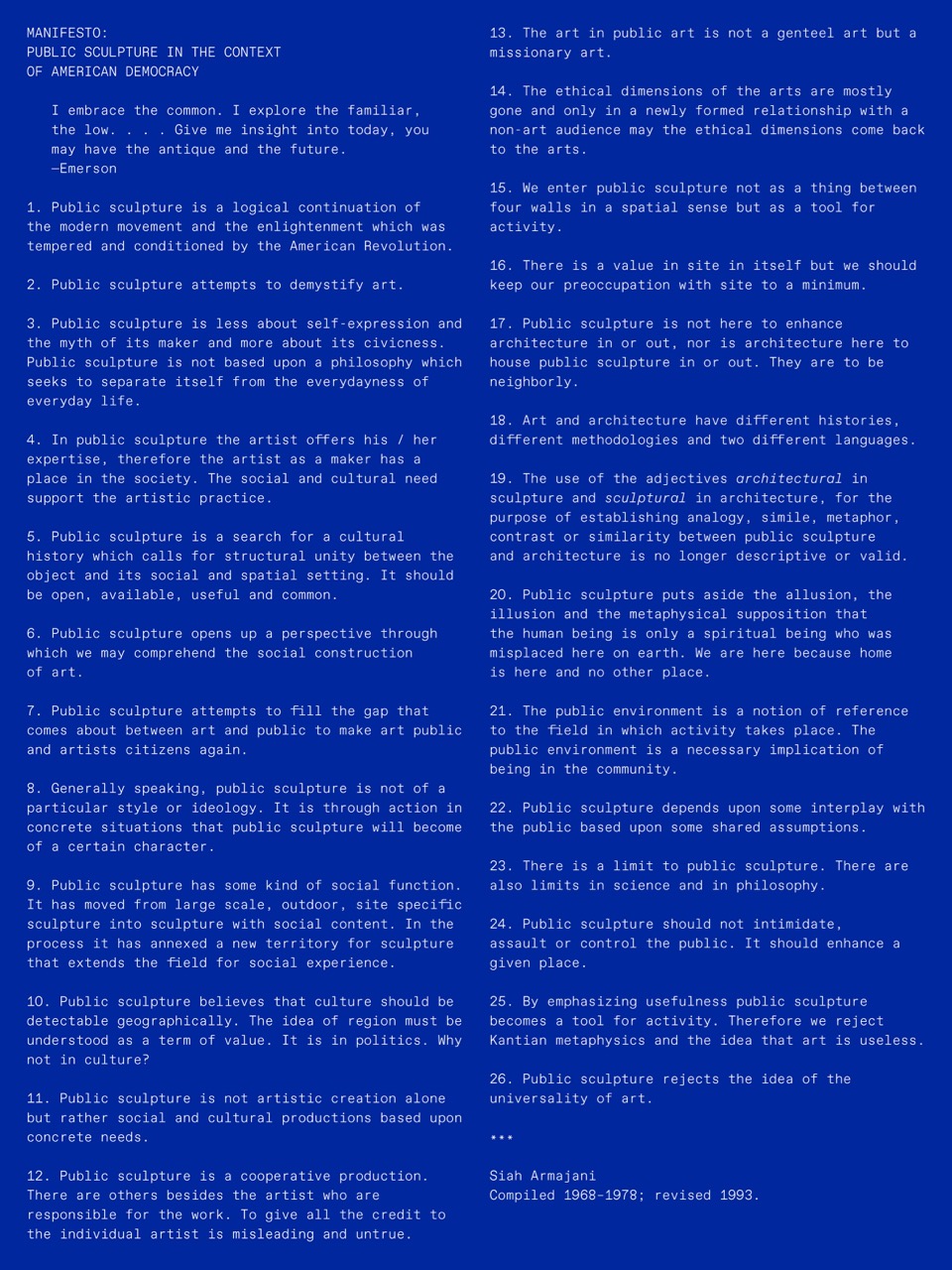

Siah Armajani has spent much of his six-decades-plus career thinking about public sculpture. A big blue poster, gathering twenty-six theses on the topic, is free for the taking in the artist’s current retrospective, Follow This Line, at the Met Breuer. Begun in 1968, eight years after the artist moved from Tehran to Minneapolis, the manifesto rings with civic language: “Public sculpture attempts to demystify art,” it claims. And: “By emphasizing usefulness public sculpture becomes a tool for activity.” But how are we to square these soaring statements with the droll proposals that Armajani launched at the same moment?

Siah Armajani, Manifesto: Public Sculpture in the Context of American Democracy, 1968–78 / 1993. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A project from 1969 proposes a tower that, if built, would cast a shadow across the width of North Dakota. To call it mystifying would be an understatement; in no way is it a tool for activity. Other works from the time are similarly quixotic. A Number Between Zero and One (1969), a tower of printing paper housed in metal armature that first appeared in the Museum of Modern Art’s conceptual exhibition Information, returns today as a precarious artifact, its sheaths of paper transformed into a kind of geological strata. From this work one would be hard-pressed to guess that a few years later Armajani would be proposing outdoor sculpture for bucolic landscapes or that the artist started his career making the beautiful text-based manuscript-like artworks combining traditions of Islamic art with nationalist politics that open the exhibition. Ca. 1970, it seems, was Armajani’s Year Zero, marking a caesura between past and future. After nearly a decade of exile, he seems to have been determined to leave his native language and traditions behind in order to embrace the new idioms—bureaucratic, civic, architectural—espoused by his adopted home. That said, he never took these new languages for granted—each convention served as an opportunity for questioning—and, more than a decade later, references to Iran would begin to reappear in his art.

Siah Armajani: Follow This Line, installation view. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pictured, left: A Number Between Zero and One, 1969.

A year after Armajani assembled A Number, he began to reorient his practice from an emphasis on the vertical axis of towers to the horizontal one of bridges. That’s when he crafted Bridge for Robert Venturi, a small wooden model and one of the first of his many works dedicated to crossings and spans (unfortunately this work has not made it from the Walker Art Center, where the exhibition premiered). Named for the postmodern architect who championed “ugly and ordinary” architecture (“Main Street is almost alright,” Venturi once quipped), Armajani’s darkened bridge evokes an everyday industrial ur-form. Like a handmade Erector set, it displays a modernist love of engineering, as well as a sense of history. This is only one of many tectonic pieces that Armajani would construct over the course of his career, a number of which are arrayed on pedestals and ledges throughout the Breuer. There are bridges marking times of day (Morning Bridge, Noon Bridge, Night Bridge), as well as urban phenomena (Dead End Bridge, House above the Bridge), with the smallest measuring a couple feet or so, and the biggest reaching some three hundred and seventy-five feet. (A version of Armajani’s Bridge over Tree, 1970, is currently vaulting over a fir in Brooklyn Bridge Park).

Siah Armajani, Bridge over Tree, 1970. Balsa wood, enamel paint, model tree, and sandpaper, 8 × 10 × 34 inches. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

While some of Armajani’s bridges can be traversed by foot, most are too small to navigate, and anyway, they don’t join anything besides one spot of the white cube to another. They speak less of real journeys than the idea of connection. Unlike the scale replicas that Chris Burden made in the 1980s and 1990s, Armajani’s creations do not so much mimic real-life structures as commit to their status as models, doing their work on the level of imagination, and in this they reach back to a utopian, even aspirational strain of artmaking, perhaps most closely associated with Tatlin’s revolutionary, nautilus-like Monument to the Third International from 1920. Yet, Armajani’s work also has a homegrown quality: his Dictionary for Building (1974–75), a hundred-plus inventory of architectural language (closets, ladders, and windows abound), allows us to contemplate different ways in which the world might come together by offering it up as a kit of discrete parts.

Siah Armajani, Dictionary for Building: Night, Morning, Noon Windows, 1974–75. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Despite his predilection for the model, Armajani has also made a number of works meant for use. In the mid-’80s he began to fabricate odd quasi-constructivist structures sized to the human body, some of which are meant for reading, others for more opaque forms of sociability. Collaborating with architects, he also took his vision outside: his variegated bridges cross highways everywhere from Minneapolis to Manhattan’s west side. The problem of how to fashion an indoor retrospective for an artist who has worked so frequently in the public sphere, on university campuses and in sculpture parks, is a vexed one, but even gallery-based work occupies an uneasy position, its David Smith–like compositions of abstract-ish forms sitting strangely with its socially engaged ethos. Like Venturi’s early book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966), Armajani’s work is “both/and” rather than “either/or.” It is both social and formal, colorful and austere, and as a result it often takes discordant, unexpected shapes. Many works from the ’80s, such as Sacco and Vanzetti Reading Room #3 (1988), dedicated to the early-twentieth-century anarchists and wonderfully installed in a side gallery, combine furniture and architectural features into dour follies, and seem to anticipate the turn to relational aesthetics in the early ’90s. But where the latter movement, typified by Jorge Pardo’s fun houses and Carsten Höller’s snaking slides, spoke of leisurely micro-utopias, Armajani’s stilted, distinctly awkward tableaus carry the disciplinary air of an eccentric principal’s office. Armajani might be the last artist to imagine that uncomfortable chairs could lead to a more engaged citizenry.

Siah Armajani: Follow This Line, installation view. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pictured: Sacco and Vanzetti Reading Room #3, 1988.

Though made in the middle of Armajani’s career, this sprawling work bears nothing so much as the traits of what Edward Said called “late style”; it is characterized by “intransigence, difficulty, and unresolved contradiction,” and the works that came after only continued further along this path. Take the spiraling steps of Armajani’s Persian Garden #1, (1983), a public design so complex that it could never be anything but a model, or his Tomb for John Berryman (1972–2012), which presents a maquette of a gothic Main Street atop a pedestal of strutting white I-beams (Tomb for Frank O’Hara, 2015, not included in the Met exhibition, plunges chair parts through a couple ordinary kitchen tables). In many ways the artist’s oeuvre is stuck between modernist ideas of difficulty and postmodern criteria of accessibility, but this conflict is also what lends the work its dignity. Armajani’s practice faces up to perhaps unresolvable quandaries: it asks, openly, whether aesthetic experience can instigate political reform, and if ambiguity might lead to greater social awareness than sloganeering. Its refusal to resolve such questions might be what makes his sculptures feel out of step with the present; indeed, it troubles many of the commonplaces of our contemporary moment: that identity should be immediately accessible, that information should be easily understood. It is this very quality that makes the work important to look at today—not as something necessarily good, but as a site of struggle.

Alex Kitnick, Brant Family Fellow in Contemporary Arts at Bard College, is an art historian and critic based in New York. His writing has appeared in publications ranging from October to May.