Jennifer Krasinski

Jennifer Krasinski

Tender takedowns: a collection of criticism by the notorious Gary Indiana.

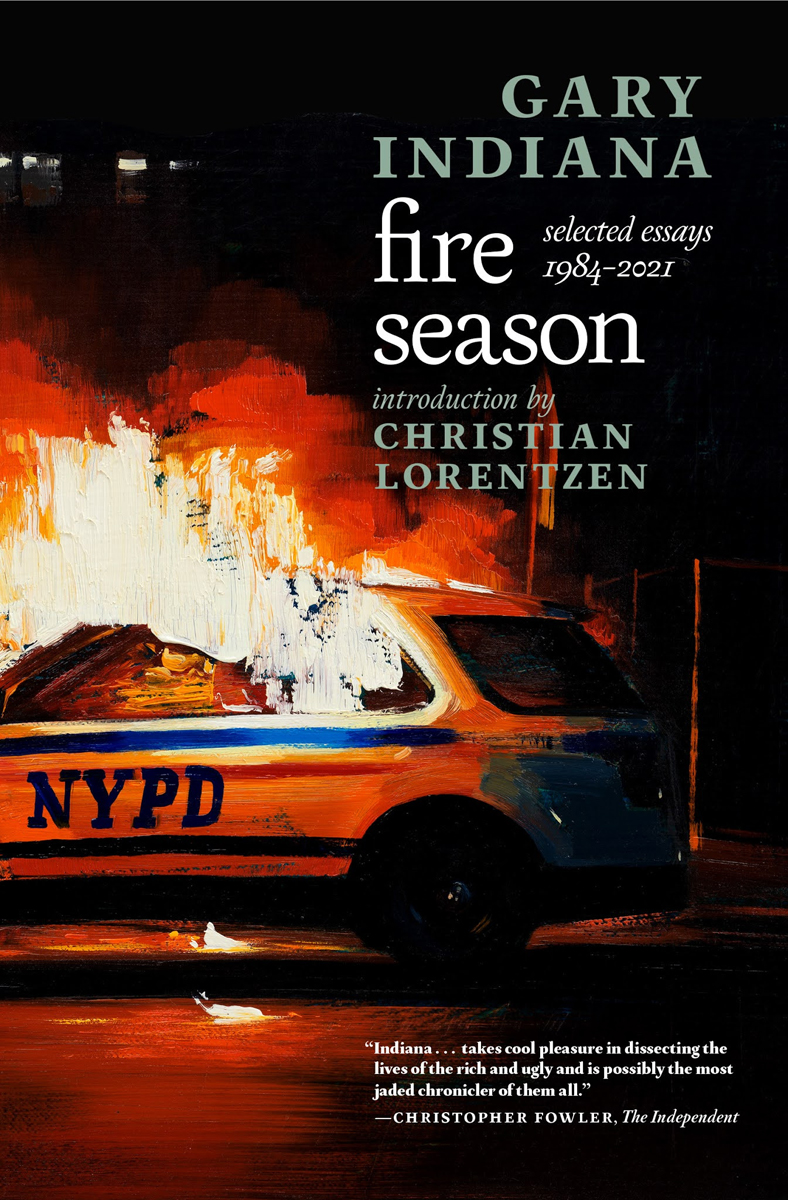

Fire Season: Selected Essays 1984–2021, by Gary Indiana,

Seven Stories Press, 352 pages, $24

• • •

The intellect of playwright, novelist, essayist, and critic Gary Indiana is notoriously brawny and sure-footed, ranging across, to borrow his words, “the queasy context of the modern world” with an assurance and elegance largely unfamiliar to our era’s torrential toadyism and its twin, cancellation. “His essays are humane to the core,” Christian Lorentzen rightly insists in his introduction to Fire Season: Selected Essays 1984–2021—a triumphant collection of thirty-nine pieces by Indiana on art, cinema, and books, as well as missives from various political and cultural terrains near to the end of civilization—noting the compassion that often goes overlooked by Indiana’s critics in favor of focusing on his haute contempt. Appreciated on the level of his sentences alone, Indiana is a lapidary wielding a straight razor, and here it feels imperative to mention that he is an expatriate of the Village Voice, for decades a prodigious hothouse of ingenious American critics. (As proof, see Vile Days, published by Semiotext(e) in 2018, a knockout compendium of his art columns for the paper.) Although he’s always lumped in with the East Village scene, Indiana’s work would be better placed alongside that of his more widely celebrated peers, many of whom, I note, are no longer among us: Joan Didion, George Trow, Serge Daney, Susan Sontag. All to say that while Indiana has always possessed his inimitable roar, he didn’t always appear as solitary as he does right now in the literary landscape.

Like Sontag—once his (albeit complicated) friend, and about whom he writes movingly in his 2015 memoir I Can Give You Anything but Love—Indiana’s tastes run most often to art and artists from across the pond. “Personally, few blue-ribbon cultural products occupy my consciousness with anything like the force of my own imagination or experience,” he admits, which may explain why it takes the mighty ranks of filmmakers such as Luis Buñuel, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Daniel Schmid, and Robert Bresson, and writers Pierre Guyotat, Jean Echenoz, Unica Zürn, and Paul Scheerbart, to hold him enrapt and move him to praise. Fire Season is in fact full of admiration, even terrific tenderness, for many of its subjects, proving throughout what an exacting reader he is of character. No contradictions are left unturned. In an elegy of sorts for the assassinated Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, Indiana registers a faint shock of learning that she who witnessed unimaginable atrocities could still experience delight. “One wishes she had had more time for selfish pleasure, less responsibility,” he offers with detectable melancholy. Indiana is never sentimental, but he does grieve. How else to think through the decimations of a life, of a life’s work? Utterly exquisite is “A Coney Island of the Viscera,” a remembrance of artist Louise Nevelson, a “hilarious terror” whom he says he loved as much as he was capable, and she him. In her, he saw his own reflection, one that wasn’t altogether flattering to either. “We were both intellectually combative, anxiety-ridden, insecure, depressive, and wretchedly insomniac,” he recalls, “and we both sported egos prone to inflate like dirigibles, then shrink to pea-size within the span of a sneeze.”

Such vulnerable admissions—these compassionate allowances—are ironically what point to the roiling moral center of Indiana’s notorious takedowns. His is not a demand for perfection or to service some simpering ideal; rather, he rages most ferociously against deceit, hypocrisy, and the dirty dealings of power. What becomes clear in reading this collection is that American culture is so habituated to bright-siding, readers can lose sight of the fact that venom, administered appropriately, is medicine, or at least an inoculation against future sickness. A child of the ’60s, Indiana reserves his most potent shots for the delusions of virtue particular to America. To that vapid wail that now becomes mantra every time this frail democracy encounters itself unretouched—how did we get here?—Indiana replies time and again, but here is where we have always been. “How different the US might be,” he writes in 2013, “. . . if every school child were taught the actual history of the country, instead of being stuffed with platitudes glorifying the supreme greatness and goodness of the place where he or she happened to be born.” Three of the book’s most formidable pieces are Indiana’s accounts of Branson, Missouri (“the tightest little cultural sphincter you are likely to find in the United States”); Euro Disney (“modeled like a concentration camp”); and the retrial of the four white police officers who pulverized Rodney King, a display of racist projections so antithetical to any claims of sanity and justice that it is “rather like seeing the Zapruder film while someone explains how John F. Kennedy assassinated Lee Harvey Oswald.”

Although Indiana’s eviscerations possess something of the sangfroid of an autopsy report, he is—to hyperextend the critic/coroner analogy—always at his face-twisting funniest when bringing out the cultural deadweights. Rest in peace, biographer Blake Gopnik, “whose elephantine, ill-written, nearly insensible Warhol has now been unleashed, weighing in at nine hundred pages, any two of which suggest nothing so much as an incredibly prolonged, masturbatory trance of graphomania.” A moment of silence for Errol Morris, who “has a definite flair for turning humans into talking sea cucumbers obsessed with philosophical or historical matters clearly beyond their intelligence.” To the loved ones of Janice Knowlton, author of Daddy Was the Black Dahlia Killer (1995), who “seems to have channeled a rich vein of snuff pornography while gazing at healing crystals in some quack’s office”: my sympathies.

Giggling, shuddering, even at times a little nauseous, I found myself only once dissenting from Indiana, not because of his point-blank candor, but because I perceived him to humble himself uncharacteristically and unnecessarily. On the painter Sam McKinniss: “he is so out of the ordinary, and so unusually well equipped to write about himself if he cared to, that writing about him feels presumptuous.” But Indiana’s got it all wrong there. Presumptuousness isn’t his cross to bear. As he himself has noted, tipping his hat to Renata Adler in his “ ‘Garbage, the City and Death,’ Etc.” (collected in Vile Days), hyperbole signals many things inside a text, one of which is a writer’s exhaustion—which leaves me wondering about Indiana’s own exhaustion regarding the business of cultural criticism, a practice woefully beholden to the world’s imagination, and to its lack thereof. Per Indiana: “Today’s MacArthur genius is tomorrow’s Edna Ferber.” A critic cannot write about what has not been created, about what is not here, but the best of them, like Indiana, stoke their readers’ desires for more art, books, films—any and all forms that would earn that thinker’s praise. Indiana’s hungry readers will devour these essays and lick their chops, feeling satisfied as they wait for more from him.

Jennifer Krasinski is a writer and critic, and the digital editorial director of Artforum.