Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

A new biography explores the link between the poet’s mania and creativity.

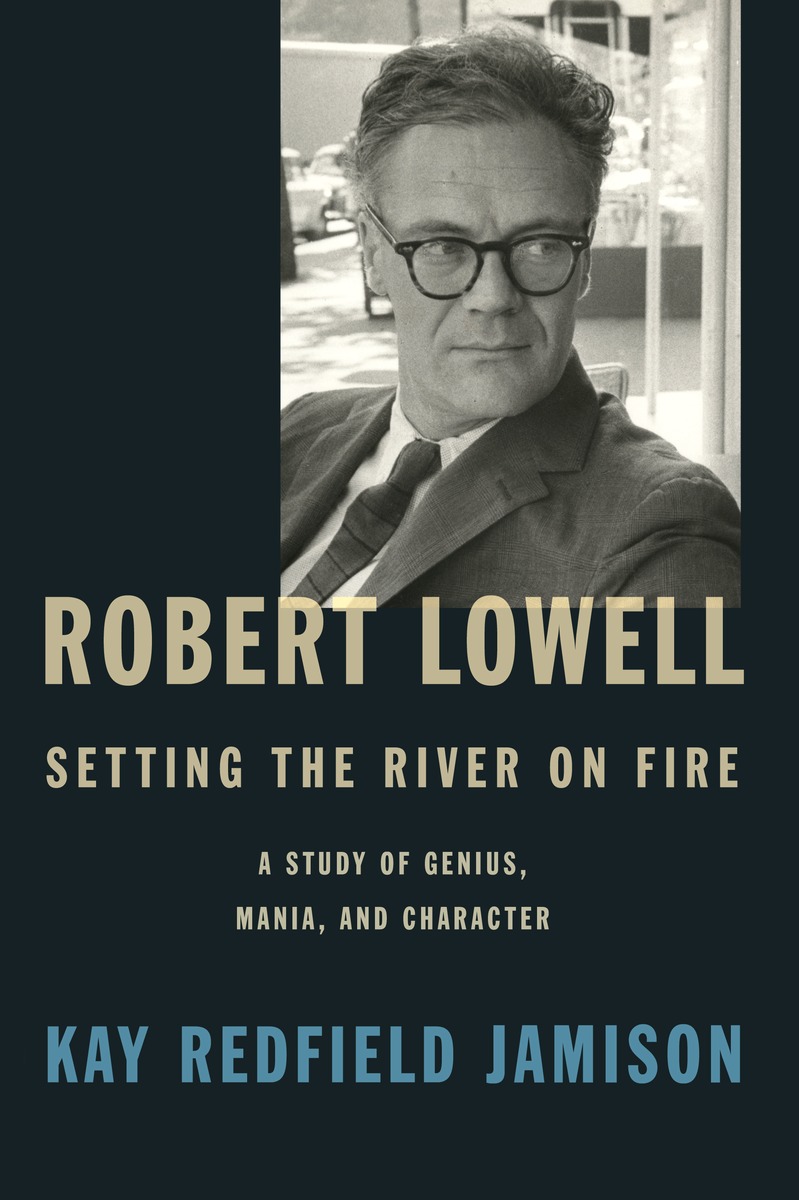

Robert Lowell: Setting the River on Fire, by Kay Redfield Jamison, Knopf, 532 pages, $29.95

• • •

Robert Lowell: Setting the River on Fire is not exactly a biography, nor a first-person account of the author’s obsession with a particular writer. Instead, Kay Redfield Jamison uses Lowell’s life as a way into a troubling question of her own: how to live and write with manic-depressive illness. She is not primarily interested in Lowell the large—or, these days, large-ish—figure on the American poetic landscape, but in the unhappy man who in “Skunk Hour” muttered, “My mind’s not right . . . /I myself am hell.”

Jamison is a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, a MacArthur recipient, a compelling memoirist whose book An Unquiet Mind (1995) described her own history of bipolar disorder. In Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament (1993), she speculated on links between manic depression and artistic creativity, looking at a number of Western artists and writers, from the usual suspects—Van Gogh, Woolf, Plath, Delmore Schwartz—to Tennyson, Herman Melville, and Mark Twain. Her new book draws on her personal and scientific knowledge of mania to give an idiosyncratic yet sensitive account of mental illness in Lowell’s life and work.

She begins by introducing the Lowells, an old New England family known for producing businesspeople, poets, and mental cases. (It’s the link between the last two she wants to talk about, though the correlation poetry–trust fund seems worth noticing as well.) Robert Lowell was born in 1917 into an undistinguished, rather loveless branch of the clan, dropped out of Harvard to study poetry, read voraciously, and fought—as he told Elizabeth Bishop in their long, warm correspondence—“to bring together in me the Puritanical iron hand of constraint and the gushes of pure wildness. One can’t survive or write without both but they need to come to terms.” He won the Pulitzer Prize at thirty; his poems were hailed as exposing the complacency and materialism of American life. In Life Studies (1959), he laid bare his own life and troubles and became the first of the confessional poets.

Jamison picks and chooses moments in Lowell’s life in ways that can feel digressive and arbitrary, breezing past his poetic apprenticeship and his ill-fated, alcohol-soaked early marriage, but looking closely when, at thirty-two, Lowell was hospitalized with his first full-blown manic attack. He had been fascinated as a child with Napoleon’s military campaigns, knowledge that came in handy whenever he believed he was Napoleon, though he at times thought he was any number of heroic figures. “What can you do after having been Henry VIII?” he wrote a friend. Jamison argues that it’s not only the energy of mania that enables poetry but its delusions, which reveal to the suffering mind “imagined worlds that are so intense, so believable, so wonderful, so terrifying” that the poetic imagination “must then expand and create to comprehend what has happened. Psychosis compels that a bridge be built, that the mind invent a way from madness back to sanity.”

Hospital records and psychiatrists’ reports help Jamison paint a picture of Lowell’s illness. But she delves just as deeply into his self-control: she wants to know how he managed to live with a mind in such frequent crisis. For much of his adult life he had an episode almost every year in which he would start affairs, insult strangers, wound his friends, then spend a month or two in an institution to emerge depressed, remorseful, and frightened of the next attack. He kept going, she believes, on will and courage, while his character and his appetite for work helped him to write despite his illness.

Another factor was his gift for love and friendship. His friends and family loved him not only for his dazzling conversation, his rumpled, chain-smoking good looks, the energy and authority that put him at the center of the American cultural scene, but for his kindness, his loyalty, his affection toward his own and others’ children. Derek Walcott speaks of “the sort of gentle, amused, benign beauty of him when he was calm.” Seamus Heaney says, “You never felt quite safe with him but neither did you ever feel sold short.”

Like everyone else, Jamison shakes her head when Lowell, in 1970, leaves his sensible and supportive second wife, Elizabeth Hardwick, for the unstable heiress Lady Caroline Blackwood. At fifty he had started taking a new drug, lithium, which stabilized his moods. He seems to have celebrated, first with political action, campaigning against the war in Vietnam, but then by staging the most banal of breakdowns, a midlife crisis. He repented, but too late: mania, alcohol, and cigarettes had taken too great a physical toll. At sixty, on his way to move back in with Hardwick in New York, he died of heart failure in a taxi from the airport.

Of all Lowell’s biographers, Jamison is clearly the best equipped to sort out how much of Lowell’s complex character was himself and how much was mania. Yet in this intriguing, strangely structured book (which includes a critique of Thoreau’s influence on Lowell and a scientific paper on bipolar illness, among other digressions), there’s one question the author never asks. She emphasizes that many of the great midcentury poets, most of them Lowell’s friends—John Berryman, Anne Sexton, Randall Jarrell, Theodore Roethke—suffered from bipolar disorder. Along with the alcoholic Dylan Thomas, they were read and admired partly because they were what postwar America thought poets should be: out of their mind. Why, at that moment, was there such an eager audience for their lunacy? Did the conservative citizens of the postwar years long for a channel to the mind of the mad? Did they want poets to be wild so they didn’t have to? Or did they find personal pain less threatening than the voices of collective pain and anger that were struggling to make themselves heard?

I wished Jamison’s gaze would widen, to take in not only the generative power of mania but also its appeal at a certain historical moment. But though her focus on Lowell’s own experience of his illness narrows her approach, it deepens it, too. There may be no other writer who could shed so much light on Lowell’s private dysphoria or the public courage of his persistence.

Julie Phillips is the award-winning author of James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon. She lives in Amsterdam, reviews fiction for the Dutch newspaper Trouw, and is working on a biographical book about creativity and mothering. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Ms., and The Village Voice, among others. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.