Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Reliving a 1949 murder, Adania Shibli’s novel pursues what makes

a story true.

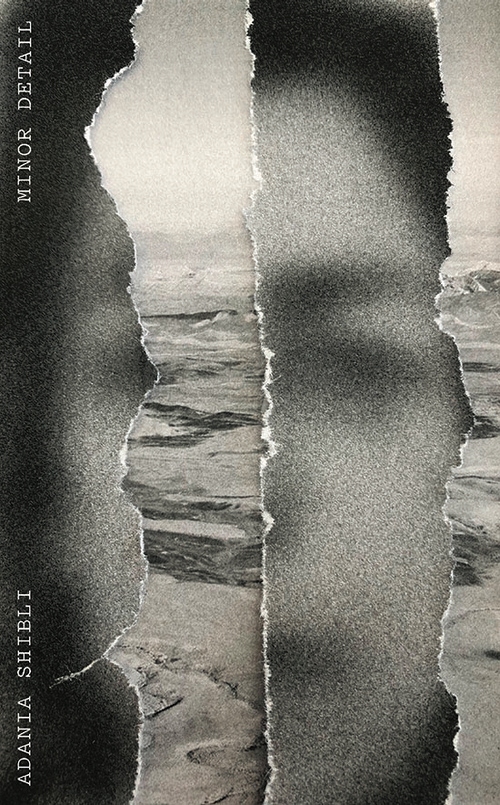

Minor Detail, by Adania Shibli, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette,

New Directions, 105 pages, $15.95

• • •

The main characters in Adania Shibli’s fiction suffer all kinds of real and imagined maladies. They stutter. They stumble. They develop serious ear infections and catch weird strains of flu. They are stung by venomous (possibly nonexistent) creatures who drive them insane. Outrageously clumsy, Shibli’s protagonists are crippled by anxiety and defiantly stubborn—so much so that when pushed, they either trespass incredibly dangerous boundaries or withdraw into silence, letting the world around them collapse.

With Minor Detail, her explosive double-telling of a single crime story, first published in Arabic in 2016, Shibli has written three brisk novels in fifteen years. Each is under 150 pages, the language stripped down to irreducible details, the narrative built up from a pattern of glinting images. Shibli’s debut, Touch, published in Arabic in 2001, translated into English in 2010, follows a young girl’s awakening through five breathtaking sections—gorgeous ruminations on themes such as color and language—while news of the Sabra and Shatila massacre in Lebanon seeps in from the novel’s edges. We Are All Equally Far from Love, published in Arabic in 2004, translated into English in 2012, creates a kaleidoscope of interlocking parts, which combine to tell a vicious story of infidelity, betrayal, stolen letters, and an insufferable teenage postal worker named Afaf.

Besides Afaf, none of Shibli’s main characters are named. All of them are women. Or most of them. Or perhaps their gender hardly matters. What does matter are the unexpected, even shocking ways in which her protagonists respond to the forces of constriction and confinement, the waves of dispossession and disorientation, that are constantly rushing over them.

Minor Detail is Shibli’s most ambitious novel to date. The plot hinges on a murder. In the summer of 1949, a platoon of soldiers sets up camp in the southwest Negev desert to secure Israel’s border with Egypt and comb the area for remaining Arabs, most of whom have been killed or forced out by heavy shelling. One day, the soldiers discover a group of Bedouin and open fire, killing everything in sight except a barking dog and a weeping young woman. They bring the woman back to their encampment, hose down her body, cut off her hair, and dress her in a military uniform. Then they rape her, kill her, and bury her in the sand.

Simpler in structure than Shibli’s previous novels, Minor Detail is divided in two equal parts. The first, set in 1949, introduces the Bedouin woman’s murder through the officer in charge of the Israeli platoon. Shibli lures readers into his account by repetition. We follow the soldier’s daily routines as he bathes, dresses, and scans his room for aberrations. But no matter how exacting his behavior, he moves through the novel in a state of crazed delirium. One night, he wakes to find a creature resting on his upper left thigh. He lunges for it and it disappears, leaving behind a menacing wound. Shibli holds out the possibility that he commits his crime in part because he has been poisoned by something truly evil.

The second part of Minor Detail, set closer to the present day, recounts the same murder, discovered a quarter of a century later by a deeply neurotic woman in Ramallah. A loner and a misfit, she struggles mightily with the idea of crossing borders, including the threshold of her own home. Before leaving for work each day, she sits at a table, gazes out the window, and toils away on a vague project that sounds like writing but serves as procrastination, even paralysis. Some days she never leaves at all.

Scouring the newspapers one morning, she comes across a mention of the Negev murder. She is struck most by the date. “A group of soldiers capture a girl, rape her, then kill her, twenty-five years to the day before I was born;” Shibli writes, “this minor detail . . . will stay with me forever; in spite of myself and how hard I try to forget it, the truth of it will never stop chasing me.”

Shibli’s protagonist insists the violence of the story is commonplace. Rape and murder happen all the time, she argues, and not only “in a place dominated by the roar of occupation and ceaseless killing.” It’s really only narcissism that draws her to it, she says, the fact that the incident took place on her birthday, albeit at a twenty-five-year remove (like Shibli, she was born in 1974.) But this simple coincidence sets the protagonist off on a terrifying detective search for a fuller version of the victim’s story.

She calls the journalist who wrote the initial article. Impatiently, he tells her he knows nothing more and directs her to a series of military museums and archives in Tel Aviv. She doesn’t have a car, nor does she possess the right identity card to access those institutions. Despite her reticence, she borrows a colleague’s ID and dives into a harrowing maze of checkpoints, restricted areas, and bewildering construction. The deeper in she goes, the more that maze seems to fold in on her like a trap. She risks arrest, torture, death—but she keeps going, crashing through whatever barriers appear in her path.

A critic and occasional curator as well as a novelist and playwright, Shibli is an intensely visual writer. The extreme economies of her style—blending aphorism and enigma, dry humor and searing critique—recall the novellas of César Aira and Mario Bellatin, two writers equally loved by artists, as well as the later prose works of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. But the first part of Minor Detail is so vividly composed that it almost reads like cinema, bringing to mind scenes from Claire Denis’s landmark film Beau Travail.

In the second part, Shibli’s supreme attentiveness to the landscape, to the grotesque details of the outer world and her character’s peculiar way of seeing them, nearly obscures the novel’s inner purpose—which is to question, provocatively and on several levels (literary, philosophical, political, forensic), what makes a story true. Many possible answers present themselves in Minor Detail, ranging from the strictly objective (numbers, dates, documents) to the wildly subjective (believability, emotional resonance, ideological usefulness). To Shibli’s great credit, she leaves the question open as the plot takes over.

Shibli’s protagonist finds nothing in those museums. She cannot tell the victim’s story by documentary means. It demands imagination and, on the part of the author, a boldly anachronistic interpretation of events. As the protagonist becomes further lost and more perilously stranded, the space between the two narratives suddenly crumbles. She comes to embody the victim and enact her ordeal. She is clearly, inexorably, being drawn to the black hole of the crime scene. In the novel’s astonishing last pages, she crosses a final line to a place of pure terror. Minor Detail ends brutally. But in the act of writing such an evocative, tightly wrought fiction, in her invention of such a complex, fighting character who is at once the victim’s double and the author’s stand-in, Shibli not only reflects the deadening conditions of occupation. She also, crucially, transcends the damage they have done.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer and critic who divides her time between Beirut and New York. A contributing editor for Bidoun, she writes regularly for publications such as Artforum, Afterall, Aperture, and frieze. Her first book, Etel Adnan (Lund Humphries), on the paintings of the Lebanese-American poet Etel Adnan, was published in 2018. She spent fifteen years working as a journalist in the Middle East, focusing on the relationship between contemporary art and political upheaval.